What is superficial spreading melanoma?

Superficial spreading melanoma is the most common type of melanoma, a potentially serious skin cancer that arises from melanocytes (pigment cells) along the basal layer of the epidermis.

Superficial spreading melanoma is a form of melanoma in which the malignant cells tend to stay within the epidermis (‘in situ’ phase) for a prolonged period (months to decades). At first, superficial spreading melanoma grows horizontally in the skin – this is known as the radial growth phase, presenting as a slowly-enlarging flat area of discoloured skin.

An unknown proportion of superficial spreading melanoma become invasive, that is, the melanoma cells cross the basement membrane between the epidermis and dermis and malignant melanocytes enter the dermis. A rapidly-growing nodular melanoma can arise within superficial spreading melanoma and proliferate deeply within the skin.

Management of melanoma is evolving. For up to date recommendations, refer to Australian Cancer Council Clinical practice guidelines for the diagnosis and management of melanoma.

Who gets superficial spreading melanoma?

According to New Zealand Cancer Registry data, 2256 invasive melanomas were diagnosed in 2008; 48% were in males. At least 40% were reported to be superficial spreading melanoma. There were 371 deaths from all types of melanoma in 2008 (69% were male).

Superficial spreading melanoma accounts for two-thirds of cases of melanoma in Australia and New Zealand. It nearly always arises in white skinned individuals. Although more common in very fair skin (skin phototype 1 and 2), it may also occur in those who tan quite easily (phototype 3). It is rare in brown or black skin (phototype 4-6).

Superficial spreading melanoma is equally common in males and females. Only 15% of melanomas arise before the age of 40, and it is rare under the age of 20 (<1%).

The main risk factors for superficial spreading melanoma are:

- Increasing age (see above)

- Previous invasive melanoma or melanoma in situ

- Previous nonmelanoma skin cancer

- Many melanocytic naevi (moles)

- Multiple (>5) atypical naevi (funny-looking moles or moles that are histologically dysplastic)

- Strong family history of melanoma with 2 or more first-degree relatives affected

- Fair skin that burns easily

- History of blistering sunburn(s).

Less strong factors include blue or green eyes, red or blond hair, indoor occupation with outdoor recreation, and signs of sun damage.

What is the cause of superficial spreading melanoma?

Superficial spreading melanoma is due to the development of malignant pigment cells (melanocytes) along the basal layer of the epidermis. The majority arise in previously normal-appearing skin. About 25% develop within an existing melanocytic naevus, which can be a normal common naevus, an atypical or dysplastic naevus, or a congenital naevus.

What triggers the melanocytes to become malignant is not fully known. Specific gene mutations such as BRAFV600E have been detected in many superficial spreading melanomas and these mutations may change as the disease advances.

Damage by ultraviolet radiation results in a degree of immune tolerance, allowing abnormal cells to grow unchecked. This can occur from exposure to natural sunlight, particularly if sunburn has occurred, and artificial sources of ultraviolet radiation from sun beds / solaria.

What are the clinical features of superficial spreading melanoma?

Superficial spreading melanoma tends to occur at sites of intermittent, intense sun exposure, especially on the trunk in males (40%) and the legs in females (also 40%).

Superficial spreading melanoma presents as a slowly growing or changing flat patch of discoloured skin. At first, it may resemble a melanocytic naevus (mole), ephelis (freckle), or lentigo. It becomes more distinctive in time, often growing over months to years or even decades before it is recognised. Like other flat forms of melanoma, it can be recognised by the ABCDE signs: Asymmetry, Border irregularity, Colour variation, Different, and Evolving. The EGF (Elevated, Firm, Growing) signs indicate nodular melanoma.

Superficial spreading melanoma clinical features may include:

- Irregular asymmetrical shape

- Irregular border which may be ill-defined and smudgy in places

- Variable pigmentation: colours may include light brown, dark brown, black, blue, grey, pink, and red

- There may be skip areas that are skin coloured, or white scars due to regression

- Different - the odd-mole-out or 'ugly duckling' is different from that person's usual naevi.

- It may be larger in size than most moles: > 6 mm and often 1–2 centimetres in diameter at diagnosis: however aim for diagnosis when less than 6mm

- Change (evolution) over days, weeks, months, or years.

A rare variant of superficial spreading melanoma is the verrucous melanoma on the limbs and back of middle-aged and elderly men.

Invasive may be indicated by the following features:

- Smooth surface at first, later becoming thicker with an irregular surface

- Thickening of part of the lesion

- Increasing number of colours, especially blue or black

- Ulceration or bleeding

- Itching or stinging.

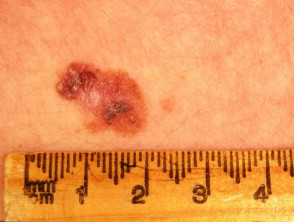

Superficial spreading melanoma

See more images of superficial spreading melanoma ...

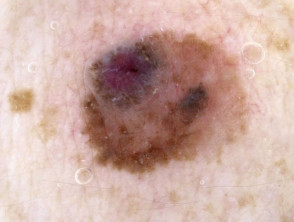

Dermoscopy of superficial spreading melanoma

- Asymmetrical structure and colours

- Atypical, broadened pigment network

- Blue-grey structures (blue-white veil)

- Three or more colours

Dermoscopy of superficial spreading melanoma

In vivo reflectance confocal microscopy of superficial spreading melanoma

- Epidermis - atypical honeycomb or cobblestone pattern, Pagetoid cells

- Dermo-epidermal junction - disorganised appearance, atypical cells

- Upper dermis - nests of round or pleomorphic cells, loss of dermal papillae

How is superficial spreading melanoma diagnosed and investigated?

Superficial spreading melanoma may be suspected clinically, aided by dermoscopy and reflectance confocal microscopy, and confirmed on skin biopsy (usually excision biopsy).

Biopsy

If the skin lesion is suspicious of superficial spreading melanoma, it should be cut out (excision biopsy). A partial biopsy is best avoided, except in unusually large lesions where multiple punch biopsies may be required. A single incisional or punch biopsy could miss a focus of melanoma arising in a pre-existing naevus.

The pathological diagnosis of melanoma can be difficult in very early lesions. Histological features of superficial spreading melanoma include the presence of buckshot (pagetoid) scatter of atypical melanocytes within the epidermis. These cells may be enlarged with unusual nuclei. Dermal invasion results in melanoma cells within the dermis or deeper into subcutaneous fat.

Extra tests using immunohistochemical stains may be necessary.

Pathology report

The pathologist's report should include a macroscopic description of the specimen and melanoma (the naked eye view), and a microscopic description. The following features should be reported if there is invasive melanoma.

- Diagnosis of primary melanoma

- Breslow thickness to the nearest 0.1 mm

- Clark level of invasion

- Margins of excision ie, the normal tissue around the tumour

- Mitotic rate – a measure of how fast the cells are proliferating

- Whether or not there is ulceration

The report may also include comments about the cell type and its growth pattern, invasion of blood vessels or nerves, inflammatory response, regression and whether there is associated in-situ disease and/or associated naevus (original mole).

What is Breslow thickness?

The Breslow thickness is reported for invasive melanomas. It is measured vertically in millimetres from the top of the granular layer (or base of superficial ulceration) to the deepest point of tumour involvement. It is a strong predictor of outcome; the thicker the melanoma, the more likely it is to metastasise.

What is the Clark level of invasion?

The Clark level indicates the anatomic plane of invasion.

| Level | Characteristics |

|---|---|

| Level 1 | In situ melanoma |

| Level 2 | Melanoma has invaded papillary dermis |

| Level 3 | Melanoma has filled papillary dermis |

| Level 4 | Melanoma has invaded reticular dermis |

| Level 5 | Melanoma has invaded subcutaneous tissue |

The deeper the Clark level, the greater the risk of metastasis (secondary spread). It is useful in predicting outcome in thin tumours, and less useful for thicker ones in comparison to the value of the Breslow thickness.

Further investigations

Those with melanoma that is more than 0.8 mm thick or more advanced primary disease may be advised to have:

- sentinel lymph node biopsy

- Blood tests, including LDH

- Imaging: ultrasound, X-ray, CT, MRI, and/or PET scan.

Tests are not typically worthwhile for stage 1/2 melanoma patients unless there are signs or symptoms of disease recurrence or metastasis. And no tests are thought necessary for healthy patients who have remained well for 5 years or longer after removal of their melanoma, whatever stage.

Staging

Melanoma staging means finding out if the melanoma has spread from its original site in the skin. Most melanoma specialists refer to the American Joint Committee on Cancer (AJCC) cutaneous melanoma staging guidelines (2009). Not all superficial spreading melanomas require formal staging with investigations.

In essence, the stages are:

| Stage | Characteristics |

|---|---|

| Stage 0 | In situ melanoma |

| Stage 1 | Thin melanoma <2 mm in thickness |

| Stage 2 | Thick melanoma > 2 mm in thickness |

| Stage 3 | Melanoma spread to involve local lymph nodes |

| Stage 4 | Distant metastases have been detected |

Should the lymph nodes be removed for superficial spreading melanoma?

If the local lymph nodes are enlarged due to metastatic melanoma, they should be completely removed. This requires a surgical procedure, usually under general anaesthetic. If they are not enlarged, they may be tested to see if there is any microscopic spread of melanoma. The test is known as a sentinel node biopsy.

In New Zealand, many surgeons recommend sentinel node biopsy for melanomas thicker than 1 mm, especially in younger persons. Although node biopsy may help in staging the cancer, it does not offer any survival advantage. The necessity for sentinel node biopsy is controversial at present.

Lymph nodes containing metastatic melanoma often increase in size quickly. An involved node is usually non-tender and firm or hard in consistency. If this occurs between planned follow-up visits, let your doctor know promptly.

What is the differential diagnosis of superficial spreading melanoma?

- Melanocytic naevus, particularly atypical melanocytic naevus

- Solar lentigo

- Seborrhoeic keratosis

- Pigmented basal cell carcinoma

What is the treatment for superficial spreading melanoma?

The initial treatment of a primary melanoma is excision; the lesion should be completely excised with a 2 mm margin of normal tissue. Further treatment depends mainly on the Breslow thickness of the lesion.

After initial excision biopsy; the radial excision margins, measured clinically from the edge of the melanoma, recommended in the The Australian and New Zealand Guidelines for the Management of Melanoma (2008) are shown in the table below. Wide local excision may necessitate flap or graft closure of the wound. Occasionally, the pathologist will report incomplete excision of the melanoma, despite wide clinical margins. This means further surgery or radiotherapy will be recommended to ensure the tumour has been completely removed.

| Thickness | Excision margin |

|---|---|

| Melanoma in situ | 5mm |

| Melanoma < 1.0mm | 1cm |

| Melanoma 1.0–2.0mm | 1–2cm |

| Melanoma 2.0–4.0mm | 1–2cm |

| Melanoma > 4.0mm | 2cm |

What happens at follow-up after a superficial spreading melanoma diagnosis?

Follow-up after a melanoma diagnosis has two aims:

- detect recurrence early

- diagnose an unrelated new primary melanoma at the first possible opportunity. A second invasive melanoma occurs in 5–10% patients with melanoma; an unrelated melanoma in situ develops in more than 20% of melanoma patients.

The Australian and New Zealand Guidelines for the Management of Melanoma (2008) make the following recommendations for follow-up for patients with invasive melanoma.

- Self skin examination

- Regular routine skin checks by patient's preferred health professional

- Follow-up intervals are preferably six-monthly for five years for patients with stage 1 disease, three-monthly or four-monthly for five years for patients with stage 2 or 3 disease, and yearly thereafter for all patients.

- Individual patient’s needs should be considered before appropriate follow-up is offered

- Provide education and support to help patient adjust to their illness

The follow-up appointments may be undertaken by the patient's general practitioner or specialist or they may be shared.

Follow-up appointments may include:

- Check the scar where the primary melanoma was removed - visual check and by palpation

- Feel for the regional lymph nodes

- General skin examination

- Full physical examination

- In those with many melanocytic naevi or atypical moles, baseline whole body imaging and sequential macro and dermoscopic images of melanocytic lesions of concern (mole mapping)

What is the outcome for superficial spreading melanoma?

Superficial spreading melanoma in situ is not dangerous; it only becomes potentially life threatening if an invasive melanoma develops within it. The rates of melanoma in situ are not reported by cancer registries. The risk of spread and ultimate death from invasive melanoma depends on several factors, but the main one is the measured thickness of the melanoma at the time it was surgically removed.

The Melanoma Guidelines report that metastases are rare for melanomas < 0.75 mm and the risk for tumours 0.75–1 mm thick is about 5%. The risk steadily increases with thickness so that melanomas > 4 mm have a risk of metastasis of about 40%.

New Zealand statistics gathered by the Cancer Registry between 1994 and 2004 revealed 15,839 invasive melanomas. Of these, 52% were less than 0.75 mm thick, 22% were between 0.76 and 1.49 mm, 15% were between 1.5 and 3 mm in thickness, and 11% were more than 3 mm in thickness. Thicker tumours were slightly more likely to be diagnosed in males, and more likely in older people than younger ones.