What is American trypanosomiasis?

American trypanosomiasis, commonly known as Chagas disease, is a systemic infection caused by the zoonotic protozoan parasite Trypanosoma cruzi.

Who gets American trypanosomiasis?

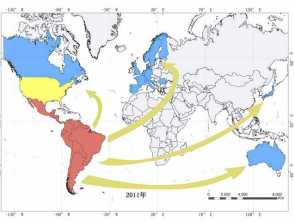

American trypanosomiasis is endemic in the southern half of the United States, and 21 countries in South and Central America. It has spread to at least 19 non-endemic countries including through Europe and the Asia-Pacific due to migration and international travel. An estimated 8–10 million people worldwide have Chagas disease, including approximately 500,000 in the US and 100,000 in Europe. In Latin America alone there are 28,000 new cases each year. The WHO estimated more than 16 million people migrated from endemic areas to non-endemic countries between the years 2000 and 2009. Active transmission has then occurred in several non-endemic countries. The majority of cases in non-endemic countries are adult Latin-Americans, most of whom are unaware of their diagnosis. Serological studies in Europe have shown an overall prevalence of 4% in immigrant Latin Americans, and 18% in Bolivians. In 2006, New Zealand had 6315 permanent residents born in endemic countries, with an estimated prevalence of Chagas disease of 98 cases. In 2011, Australia had a predicted 1928 cases in 116,430 migrants.

Distribution of Chagas disease

Red indicates endemic areas where transmission is through vectors; yellow indicates endemic areas where transmission is occasionally through vectors; non-endemic areas are in blue where transmission is vertical or via blood transfusions or organ transplants. Acknowledgement Liu and Zhou Infectious Diseases of Poverty (2015) 4:60.

What causes American trypanosomiasis?

T. cruzi is a zoonotic intracellular parasite that has been identified in pre-Columbian mummies but was only described on April 14, 1909 by Carlos Ribeiro Justiniano Chagas. The parasite spread to humans from mammalian hosts such as armadillos, rodents, and raccoons in the wild following the clearance of forests and jungles for timber and farming. Humans are an accidental host, and infections were initially noted in poor rural workers whose homes were invaded by the triatomine bugs seeking night-time blood meals, but most cases are now identified in urban areas. Domesticated animals have subsequently become infected. In Australia, the animal form of Chagas disease must be notified to the Department of Agriculture.

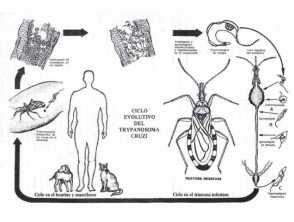

Triatomine bugs, also known as reduviid or kissing bugs, collect T. cruzi during an infected blood meal and excrete the protozoa in their faeces.

Routes of transmission of American trypanosomiasis to humans include:

- Vector spread: Following a blood meal, the triatomine bug deposits trypomastigotes in its faeces which can enter broken skin or through adjacent intact mucous membranes such as the conjunctiva

- Ingestion: Accidental intake of food/drink contaminated with infected triatomine bugs or their urine or faeces

- Transplacental vertical spread of T. cruzi from an infected mother to her baby – risk of infection 5–10%.

- Blood/platelet transfusion or organ/tissue transplantation from an infected donor – risk of infection 20–40%.

In endemic countries, spread is predominantly by triatomine bugs whereas in non-endemic countries transfusions/transplants and vertical spread are the major routes.

Trypanosoma cruzi

What are the clinical features of American trypanosomiasis?

Acute American trypanosomiasis

- Incubation period 1–2 weeks

- Asymptomatic parasitaemia

- Symptomatic – non-specific febrile illness, nausea/vomiting/diarrhoea, headache, myalgia, lymphadenitis, hepatosplenomegaly

- Vector inoculation site — chagoma at skin portal of entry, Romaña sign if entry through periorbital mucosa.

Parasitaemia resolves after 4–8 weeks and clinical features resolve in 90% of cases.

Chronic American trypanosomiasis

- Indeterminate asymptomatic Chagas disease — 60–70% — rest of life

- Cardiac/gastrointestinal chronic Chagas disease — 30-40%, develops 10–30 years after initial infection

- Chronic chagasic cardiomyopathy — 1/3, diffuse myocarditis, dilated cardiomyopathy, heart failure

- Gastrointestinal form of Chagas disease – denervation of gastrointestinal (GIT) nervous system causing dysphagia, GIT hypomotility, dilatation of colon, and constipation

- Cardiodigestive Chagas disease.

The severity of chronic Chagas disease is assessed using the Kuschnir classification system ranging from Class 0 having reactive serology, normal ECG, and heart size, through to Class 3 with cardiac enlargement and apical aneurysm.

Cutaneous features of Chagas disease

- Chagoma — red indurated swelling at skin inoculation site

- Romaña sign — purplish swelling of the lids of one eye, conjunctivitis

- Schizotrypanides — diffuse measles-like eruption.

Clinical features in special groups

Congenital American trypanosomiasis in newborns

- Prematurity, low birth weight

- Hepatosplenomegaly, jaundice

- Tachycardia

- Uncommon – chagoma, rash, oedema, lymphadenopathy, myocarditis, sepsis

Reactivation Chagas disease in immunocompromised patients

- HIV infection, organ transplant recipients, drug-induced immunosuppression

- Chagas disease is an AIDS-defining illness

- Neurological and cardiac involvement are the commonest manifestations

- May present with fever and erythematous nodules and plaques

- Panniculitis and erythema nodosum-like skin lesions have been reported

- Sequential monitoring for parasitaemia if positive serology prior to commencing immunosuppression

- Treat if parasitaemia detected.

What are the complications of American trypanosomiasis?

- Reactivation of Chagas disease — immunomodulators, HIV

- Cardiac disease — dilated cardiomyopathy, heart failure

- Gastrointestinal disease — megaoesophagus, megacolon, constipation

- Neurological disease — encephalitis, pseudotumoural mass.

How is American trypanosomiasis diagnosed?

Screening of blood/tissue/organ donors, transplant recipients, and before other planned immunomodulatory treatments

- Blood smear and serological testing — routine in endemic countries and some non-endemic areas with significant numbers of Latin-American immigrants

Acute, congenital, and reactivated American trypanosomiasis

- Circulating parasites in peripheral blood seen on thick blood smear

- Xenodiagnoses — uninfected triatomine insects are fed on the patient's blood, and their gut contents examined for parasites 4 weeks later

- Blood culture

- Detection of T. cruzi DNA by polymerase chain reaction (PCR)

- Skin biopsy — intracellular amastigotes are seen in chagomas and skin lesions of acute and reactivated Chagas disease, but not in schizotrypanides.

Chronic American trypanosomiasis

- Serology — at least two of the following tests should be positive: indirect immunofluorescence, haemagglutination, ELISA

- ECG, chest X-ray

- Other investigations as clinically indicated.

In Australia and New Zealand there are very few laboratories performing serological testing for Chagas disease and confirmatory tests have to be performed overseas. Blood services screen patients based on a questionnaire, excluding potential donors who have a history of Chagas disease, were born in an endemic area, or who received fresh blood components in an endemic area. The former should never become a blood or organ donor, and the latter two groups require negative serology before becoming donors.

What is the treatment for American trypanosomiasis?

Prevention in endemic areas

- Education

- Vector surveillance and control

- Insecticide-treated bed and window netting, building codes

- Insect repellent and protective clothing

- Vaccines are under development.

Resistance to pyrethroid insecticides was first detected in triatomine bugs in the 1970s associated with vector control failures, and has become more widespread.

Prevention in non-endemic areas

- Screening of blood and organ donors

- Diagnosis and treatment of identified cases

- Education of health professionals

Acute phase

- Benznidazole

- Nifurtimox

Chronic phase

- Role of anti-trypanosomal medications controversial

- Supportive

- Symptomatic

What is the outcome for American trypanosomiasis?

Adequate treatment in the parasitaemic phase is effective in nearly all cases. Chronic Chagas disease, and rarely acute Chagas disease, can be fatal resulting in 50,000 deaths annually worldwide, including 12,000 deaths in Latin America per year.