What is calciphylaxis?

Calciphylaxis is a condition characterised by necrosis (cellular death) of the skin and fatty tissue. It is seen mainly in patients with end-stage kidney disease. It is also sometimes called calcific uraemic arteriolopathy or calcific vasculopathy.

Calciphylaxis

Who gets calciphylaxis?

Most patients with calciphylaxis have chronic kidney disease. Other conditions associated with accelerated calcium deposition in soft tissues and at risk of calciphylaxis include:

- Obesity

- Diabetes

- Caucasian race

- Female sex

- Hypoalbuminemia

- Warfarin (an anticoagulant).

In 1981, approximately 50 cases of calciphylaxis were reported in the world literature. Today, the incidence is estimated at 1 per cent per year in patients undergoing renal dialysis.

What is the cause of calciphylaxis?

The cause of calciphylaxis is not properly understood. The primary event is occlusion of the small blood vessels in the skin by a thrombus (blood clot), which results in spreading ischaemia and skin necrosis. It is thought that the clots occur because of calcification within the walls of the blood vessels.

In chronic renal failure, it is often associated with a condition known as secondary hyperparathyroidism. The damaged kidneys don't excrete phosphate properly, which results in a build-up of phosphate in the blood, which combines with calcium. Vitamin-D levels are reduced because of kidney failure and reduced absorption through the gut. The bones become resistant to parathyroid hormone. The parathyroid glands, therefore, increase in size and produce more hormone and the amount of calcium circulating in the blood.

Calciphylaxis can occur in those with high or normal levels of serum calcium and phosphate, with or without vitamin D replacement, in dialysed patients and less often in those who have not yet commenced dialysis or in those who have received a renal transplant. It is more common in women than in men, in obese patients compared to those of normal weight, and in patients who have been taking corticosteroids or other immunosuppressive medicines.

Calciphylaxis can also occur in patients with normal kidney function. Causes of non-uraemic calciphylaxis include:

- Primary hyperparathyroidism

- Malignancy

- Alcoholic liver disease

- Connective tissue disease

- Diabetes mellitus.

High levels of matrix metalloproteinases have been described, and one theory suggests chemically altered elastin protein allows deposition of calcium on small vessels.

What are the clinical features of calciphylaxis?

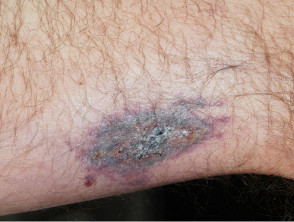

Calciphylaxis begins as surface purple-coloured mottling of the skin (retiform purpura) then bleeding occurs within the affected area. There may be blood-filled blisters. The skin goes black in the centre of star-shaped (stellate) purple lesions. The skin cells die because of lack of blood supply (dry gangrene). This causes deep and often extensive ulcers. Surgical intervention may aggravate ulceration.

Patients with calciphylaxis usually experience severe pain, burning and sometimes itching at the lesion sites.

Calciphylaxis most often occurs on the lower limb where it is one of the causes of blue toe syndrome. Lesions on the fatty areas of the trunk, abdomen, buttocks, or thighs appear to be more dangerous than lesions on the lower legs and feet.

Calciphylaxis

What are the complications of calciphylaxis?

Calciphylaxis can lead to:

- Chronic and extensive ulceration

- Secondary infection with sepsis

- Death.

How is calciphylaxis diagnosed?

A deep wedge skin biopsy may be necessary to diagnose calciphylaxis, as a similar appearance can be seen in other conditions such as necrotising fasciitis, cryoglobulinaemia, antiphospholipid syndrome, coumarin necrosis and vasculitis. Multiple biopsies may be necessary, with a risk of propagating calciphylaxis. The pathologist looks for calcium deposited within scarred and blocked blood vessels in the subcutaneous tissue. Perieccrine calcium deposition may be noted when vascular calcification is absent but may be subtle. There may also be inflammation of the fat (panniculitis). [see Calciphylaxis pathology]

X-rays of the affected limb may demonstrate vascular calcification within the skin; however, this may also be seen in healthy patients with renal disease that are not affected by calciphylaxis.

Bone scintigraphy using technetium Tc 99m bisphosphonates in patients with calciphylaxis shows increased radiotracer uptake in soft tissues throughout the body and is specifically enhanced in indurated plaques affected by calciphylaxis (but is absent in ulcers due to reduced blood flow at sites of tissue necrosis).

What is the treatment for calciphylaxis?

The best treatment for calciphylaxis is not yet clear. When it is associated with warfarin, the anticoagulant should be replaced, eg by heparin.

The initial step is to normalise the calcium and phosphate product levels and control the hyperphosphataemia associated with renal failure. A calcium and phosphate restricted diet and dialysis with a lower dialysate calcium concentration is important initial management in the calciphylaxis associated with renal failure.

In patients with a significantly elevated parathyroid hormone that cannot be medically controlled, surgical removal of the parathyroid glands (parathyroidectomy) is thought to reduce pain and promote wound healing, especially in early wound development. Parathyroidectomy should not be performed in calciphylaxis in the absence of hyperparathyroidism, as it can result in low levels of calcium in the blood and bone disease. Cinacalcet tablets can also be used to reduce secondary hyperparathyroidism.

Some patients may also be treated with anticoagulants to reduce the tendency to form blood clots, but these are not always suitable or helpful. Warfarin can be replaced by heparin in some cases.

Meticulous wound management is essential.

- Keep wounds clean.

- Surgically remove (debride) the necrotic tissue (particularly if moist) – sometimes this means a limb must be amputated.

- Systemic antibiotics are indicated if clinically infected.

Intravenous infusions of sodium thiosulfate, an antioxidant and chelator, has also been used successfully to remove the calcium. Healing occurs slowly over weeks to months. The benefit of sodium thiosulfate can be monitored using technetium Tc 99m bone scans to show a reduction in radiotracer uptake in affected areas.

Etidronate, a bisphosphonate, has been reported of benefit, but bisphosphonates may not be suitable for patients on haemodialysis.

Inhibitors of matrix metalloproteinases such as doxycycline have been reported to prevent new lesions forming.

How can calciphylaxis be prevented?

It is not known how to prevent calciphylaxis. However, patients with chronic renal failure to be under the care of a nephrologist who can monitor and treat secondary hyperparathyroidism, an identifiable cause of calciphylaxis in some patients.

What is the outlook for calciphylaxis?

Mortality in patients with calciphylaxis associated with chronic renal disease is reported to be 60–80%. Death is usually from secondary infection of the ulcers, and sepsis.

Death is less likely when warfarin is the cause of calciphylaxis, with 15 of 18 patients reported to have fully recovered.