What is colloid milium?

Colloid milium refers to a group of rare, degenerative, cutaneous deposition disorders.

The colloid degeneration disorders are characterised by amorphous, hyaline-like deposits in the dermis, which classically present as yellow–brown, semi-translucent papules and plaques over sun-exposed areas [1].

Adult colloid milium

How is colloid milium classified?

There are currently five different subtypes of colloid milium:

- Adult colloid milium

- Juvenile colloid milium

- Pigmented colloid milium

- Nodular colloid degeneration (paracolloid) of the skin

- Acral keratosis with eosinophilic dermal deposits [2].

Since colloid milium was first described as “Das Colloid-Milium der Haut” by Dr Ernst Wagner in 1866, it has also been known as colloid degeneration, colloid pseudomilium, miliary colloidoma, colloid infiltration hyaloma, and elastosis colloidalis conglomerata [3].

Who gets colloid milium?

Adult colloid milium is the most commonly occurring subtype and typically develops in fair-skinned men aged 30–60 years with an outdoor occupation, such as farming [1]. Men are four times more likely than women to develop adult colloid milium. Medical conditions occasionally associated with adult colloid milium include multiple myeloma and beta-thalassaemia [1,2].

Juvenile colloid milium is exceedingly rare. It tends to develop between 10 and 20 years of age, but it has occurred in a child aged 4 years [4]. Familial cases of juvenile colloid milium with an autosomal recessive inheritance have been reported [5].

Pigmented colloid milium usually follows the use of hydroquinone bleaching creams and extensive sun exposure. A case of pigmented colloid milium that was not associated with hydroquinone has also been reported in a Caucasian farmer with chronic exposure to fertilisers and sunlight [6].

There have been 13 reported cases of nodular colloid degeneration since it was first described in 1927; eight cases occurred in males, and the mean age was 52 years (range: 25–76 years) [7,8].

A series of six elderly Caucasians were reported to have acral keratosis with eosinophilic dermal deposits; four were male, with a mean age of 74 years (range: 59–81 years).

What are the causes of colloid milium?

Adult colloid milium is associated with exposure to excessive sunlight, petroleum, and chemicals, although its pathogenesis remains unclear. It is suspected that sunlight ruptures elastin fibres resulting in an accumulation of proteins or fibroblast products in the dermis. Contributing factors may include trauma and photodynamic effects of phenols in gas oil [3].

Juvenile colloid milium is associated with chronic sun exposure and severe sunburn, resulting in keratinocyte degeneration [4].

Pigmented colloid milium is associated with ochronosis due to hydroquinone in bleaching creams and sun exposure [1].

The role of sun exposure in nodular colloid degeneration is uncertain as a case has been described involving the penis [7]. The colloid material is suspected to relate to actinic degeneration of elastic fibres (solar elastosis) [7].

The cause of acral keratosis with eosinophilic dermal deposits is unknown. It may involve sun exposure and the regression of viral warts, although evidence for active human papillomavirus infection has not been observed [9,10].

What are the clinical features of colloid milium?

Adult colloid milium typically presents with numerous flesh-coloured or yellow–brown, semi-translucent, dome-shaped papules, that are 1–4 mm in diameter.

- Papules can coalesce into plaques.

- They tend to occur in sun-exposed areas of the face, ears, neck, dorsum of hands, and forearms.

- Unilateral involvement on the sun-exposed arm has been reported in taxi and truck drivers [2].

- A soft, golden-coloured gelatinous material can often be expressed with pressure [11].

- The underlying skin may be hypertrophic and hyperpigmented [12].

- Lesions are asymptomatic or transiently itchy [1].

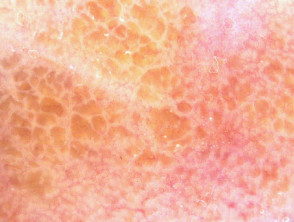

Dermoscopy reveals yellow–brown clods.

Dermoscopy of adult colloid milium

Pigmented colloid milium is characterised by grey–black clustered papules on the face [6].

Nodular colloid degeneration presents as an isolated nodule or plaque, approximately 50 mm in diameter, on chronically sun-exposed skin, particularly the face. The scalp, trunk, and extremities can also be affected [12].

Acral keratosis with eosinophilic dermal deposits presents as painless, slowly-progressive, hyperkeratotic papules on the palmar or dorsal aspects of the fingers [2,10].

What are the complications of colloid milium?

There are no systemic complications of adult colloid milium.

Juvenile colloid milium has been reported to induce ligneous conjunctivitis, a rare disease characterised by wood-like pseudomembranes developing on the mucous membrane of the eye (ocular and extraocular mucosae), and periodontitis, although the pathogenesis of these is unclear [1,14].

How is colloid milium diagnosed?

Colloid milium is confirmed by skin biopsy [12]; (see the DermNet page on colloid milium pathology). Colloid milium can be distinguished from amyloidosis and other conditions by using special stains, immunohistochemistry, and electron microscopy [1].

Histopathology of colloid milium

Histopathological features of adult colloid milium include:

- Deposits of homogenous, amorphous, faintly eosinophilic material with dividing clefts and fissures, which extend into the papillary and mid-dermis [2,3]

- Fibroblasts lining the clefts, which can contain lymphocytes and mast cells [12]

- Lack of inflammation

- Preserved adnexae (skin appendages, including sebaceous glands, sweat glands, and hair follicles) [15]

- Dilated blood vessels surrounding the colloid deposits [1,12]

- Solar elastosis with a Grenz zone separating the colloid deposits from the overlying epidermis [2,12,16]

- A flattened or hyperkeratotic epidermis [3]

In contrast to adult colloid milium, juvenile colloid milium lacks a Grenz zone and the colloid substance is found within the epidermis or superficial dermis [13].

In acral keratosis with eosinophilic dermal deposits, deposits of amorphous eosinophilic material are localised to the papillary dermis. This colloid milium subtype is not associated with elastotic degeneration (the breakdown of elastic tissue) or fissuring.

Electron microscopy

Under electron microscopy, the colloid ultrastructure appears as medium electron-dense, amorphous, granular material with short, ill-defined, branching filaments that are much smaller than those seen in amyloidosis [1,2]. Desmosome remnants, active fibroblasts, binding proteins, and nuclear proteins have also been observed [2,12].

Special stains

Adult colloid milium stains positive with crystal violet, Congo red, and periodic acid–Schiff (PAS) stains [2,11]. Adult colloid milium also stains a 'robin's egg blue' with the Pinkus' acid orcein–Giemsa stain and will fluoresce with thioflavin T [2].

Immunohistochemistry is often necessary to distinguish colloid milium from amyloidosis. Both adult colloid milium and amyloidosis stain positive for amyloid P protein. Unlike amyloidosis, adult colloid milium displays negative reactivity to cytokeratin (including MNF-116), laminin, type IV collagen, cotton dyes (including pagoda red), and light chain immunoglobulin (Ig) [11,17]. Adult colloid milium stains positively for IgG, IgM, and NKH-1 antigen (a stain for proteins related to elastic fibre microfibrils) [4].

Juvenile colloid milium does not stain for amyloid P protein but does stain positive with antikeratin and cytokeratin antibodies (including MNF116 and cytokeratin AE1/AE3) [2,13]. Juvenile colloid milium also stains positive for IgG within the colloid deposits [18]. Positive pan-cytokeratin labelling and use of electron microscopy suggest that juvenile colloid milium deposits derive from degenerate, epidermal keratinocytes in contrast to adult colloid milium, where deposits are suspected to derive from degenerate elastic tissue in the dermis [5].

Colloid islands of both the pigmented colloid milium and nodular colloid degeneration subtypes are found in the upper dermis, with fissures and clefts that extend deep within the dermis [2,6,19]. Additional yellow–brown, banana–shaped ochronotic fibres are also seen between the collagen and elastin bundles of the deep dermis in the pigmented colloid milium subtype [6].

The pigmented colloid milium and nodular colloid degeneration subtypes both stain positive with PAS and elastin stains but are negative for Congo red, in contrast to the adult colloid milium subtype [6,7].

In acral keratosis with eosinophilic dermal deposits, the deposits are positive with trichrome and PAS staining, while staining negative for Congo red, amyloid P protein, type IV collagen, and cytokeratin antibodies [2].

Histopathology of colloid milium

Histopathological features of adult colloid milium include:

- Deposits of homogenous, amorphous, faintly eosinophilic material with dividing clefts and fissures, which extend into the papillary and mid-dermis [2,3]

- Fibroblasts lining the clefts, which can contain lymphocytes and mast cells [12]

- Lack of inflammation

- Preserved adnexae (skin appendages, including sebaceous glands, sweat glands, and hair follicles) [15]

- Dilated blood vessels surrounding the colloid deposits [1,12]

- Solar elastosis with a Grenz zone separating the colloid deposits from the overlying epidermis [2,12,16]

- A flattened or hyperkeratotic epidermis [3] (See figure 1 and figure 2).

In contrast to adult colloid milium, juvenile colloid milium lacks a Grenz zone and the colloid substance is found within the epidermis or superficial dermis [13].

In acral keratosis with eosinophilic dermal deposits, deposits of amorphous eosinophilic material are localised to the papillary dermis. This colloid milia subtype is not associated with elastotic degeneration (the breakdown of elastic tissue) or fissuring.

Electron microscopy

Under electron microscopy, the colloid ultrastructure appears as a medium electron-dense, amorphous, granular material with short, ill-defined, branching filaments that are much smaller than those seen in amyloid [1,2]. Desmosome remnants, active fibroblasts, binding proteins, and nuclear proteins have also been observed [2,12].

Special stains

Adult colloid milium stains positive with crystal violet, congo red, and periodic acid-Schiff (PAS) stains [2,11] (see figure 3). Adult colloid milium stains a ‘robin’s egg blue’ with the Pinkus' acid orcein–Giemsa stain, and will fluoresce with thioflavin T [2].

Immunohistochemistry is often necessary to distinguish colloid milium from amyloidosis. Amyloid P protein is positive for adult colloid milium and amyloidosis. Unlike amyloidosis, adult colloid milium displays negative reactivity to cytokeratin (including MNF 116), laminin, type IV collagen, cotton dyes (including pagoda red), and light chain immunoglobulin [11,17]. Adult colloid milium stains positively for IgG, IgM, and NKH-1 (a stain for proteins related to elastic fibre microfibrils) [4].

Juvenile colloid milium does not stain positively for amyloid P protein but does stain positively with antikeratin and cytokeratin antibodies, including MNF116 and cytokeratin AE1/AE3 [2,13]. Juvenile colloid milium also stains positively for IgG within the colloid deposits [18]. Positive pan-cytokeratin labelling and use of electron microscopy suggest that juvenile colloid milium deposits derive from degenerate, epidermal keratinocytes in contrast to adult colloid milium, where deposits are suspected to derive from degenerate elastic tissue in the dermis [5].

Colloid islands of both the pigmented and nodular colloid degeneration subtype are found in the upper dermis, with fissures and clefts that extend deep within the dermis [2,6,19]. Additional yellow-brown, banana-shaped ochronotic fibres are also seen between collagen and elastin bundles of the deep dermis in the pigmented colloid milium subtype [6].

Pigmented colloid milium and nodular colloid degeneration subtypes both stain positive with PAS and elastin stains, but are negative for congo red, in contrast to the adult colloid milium subtype [6,7].

In acral keratosis with eosinophilic dermal deposits, the deposits have stained positive with trichrome and PAS staining, while staining negative for congo red, amyloid protein P, type 4 collagen, and cytokeratin antibodies [2].

What is the differential diagnosis for colloid milium?

The differential diagnosis of colloid milium includes other conditions presenting with multiple papules [1,11,12]. This may include:

- Milium/milia

- Sebaceous hyperplasia

- Syringomas

- Retention cysts

- Molluscum contagiosum

- Systemic and primary cutaneous amyloidosis

- Steatocystoma multiplex

- Lipoid proteinosis

- Calcinosis cutis

- Cutaneous sarcoidosis

- Papular mucinosis.

What is the treatment for colloid milium?

Treatment may include combinations of medical and physical therapies [1,11,12].

Medical therapies

Medical therapies to treat colloid milium include:

- Topical retinoids (tretinoin, isotretinoin, and adapalene)

- Keratolytic creams (urea, salicylic acid, and alpha hydroxy acids).

Physical therapies

Physical therapies to treat colloid milium include:

- Curettage and electrosurgery

- Cryotherapy

- Dermabrasion

- Carbon dioxide or erbium laser resurfacing

- Photodynamic therapy.

Excessive cautery, cryotherapy, and laser therapy may cause poor cosmetic results [3].

What is the outcome for colloid milium?

Colloid milium may become more extensive over time, but it tends to stabilise after 3 years [3]. New lesions rarely develop after this period. If left untreated, colloid milium typically persists with no spontaneous resolution [1].