What is cutaneous tuberculosis?

Cutaneous tuberculosis (TB) results from skin infection with Mycobacterium tuberculosis (M. tuberculosis), the same bacterium that causes tuberculosis of the lungs (pulmonary TB). Mycobacterium bovis caused tuberculosis in cattle, and is now a rare cause of cutaneous tuberculosis worldwide following eradication programs in cattle. BCG vaccination can be complicated by skin infection with the bacillus Calmette-Guerin (BCG), an attenuated strain of M. tuberculosis.

Who gets cutaneous tuberculosis?

Cutaneous tuberculosis is an uncommon form of extrapulmonary TB (TB infection of organs and tissues other than the lungs). Even where TB is common, such as the Indian subcontinent, sub-Saharan Africa, and China, cutaneous tuberculosis is rare (<0.1%).

Risk factors for developing tuberculosis include:

- Close contact with a patient with active TB

- Living in or visiting a country or community where TB is common

- Living in a crowded community, including institutions such as aged care residences, long-stay hospitals, and prisons

- Working in hospitals and healthcare environments.

Not everyone exposed to M. tuberculosis will develop disease as genetic susceptibility (MIM 607948) affects the development of infection; it has been estimated that 10% of those infected will develop active tuberculosis.

What causes cutaneous tuberculosis?

Cutaneous tuberculosis is nearly always caused by Mycobacterium tuberculosis, the tubercle bacillus. This is an acid-fast mycobacterium; other examples of mycobacterial skin infections include leprosy (M. leprae) and atypical mycobacterial infections such as M. marinum.

Cutaneous tuberculosis may follow:

- Direct inoculation of tubercle bacilli into the skin

- Spread to the skin via the bloodstream

- Extension into the skin from an underlying infective focus.

The immune response to the tubercle bacillus influences the clinical manifestations of infection. Prior infection with the tubercle bacillus or BCG vaccination results in moderate to high immunity. Drug-induced immunosuppression, use of TNF-alpha inhibitors, and systemic illness such as HIV/AIDS or leukaemia may allow reactivation of latent TB.

What are the clinical features of cutaneous tuberculosis?

Primary cutaneous tuberculosis

Direct inoculation of the skin or mucous membranes with tubercle bacilli from an outside source results in a tuberculous chancre. Children are predominantly affected. Infection may follow piercings, tattooing, or other penetrating skin injury. The face, hands, and legs are the commonest sites involved. The tuberculous chancre appears 1-4 weeks after inoculation, presenting initially as a firm red papule which becomes a painless shallow ulcer with a granular base and undermined edge. Sporotrichoid lesions and enlarged regional lymph nodes can develop.

Rarely, infection can occur following use of the BCG bacillus vaccine used to immunise against TB, producing BCG vaccination-induced lupus vulgaris. STAT1 mutation may result in a susceptibility BCG infection. Individuals who are on TNF alpha inhibitors, and infants born to mothers exposed to TNF alpha inhibitors in pregnancy must not receive BCG as they are at risk of developing disseminated BCG infection.

Reinoculation/reinfection cutaneous tuberculosis

Lupus vulgaris is the most common presentation of reinfection cutaneous tuberculosis. Any skin site can be involved, but the head and neck are the most commonly reported affected sites.

Lupus vulgaris

Tuberculosis verrucosa cutis (warty tuberculosis) occurs after direct inoculation of tubercle bacilli into the skin of someone who has been previously infected and developed good immunity. It was called 'prosector's wart' when it followed accidental injury in the autopsy room.

Tuberculosis verrucosa cutis

Orificial tuberculosis (tuberculosis cutis orificialis) follows autoinoculation from advanced internal disease depositing tubercle bacilli at mucocutaneous junctions such as around the nose and mouth.

See more images of tuberculosis ...

Haematogenous spread to the skin

Miliary tuberculosis follows generalised spread of tubercle bacilli via the bloodstream from an active internal focus of tuberculosis. It is seen mainly in children and immunocompromised patients. Skin involvement is called disseminated cutaneous tuberculosis or acute cutaneous miliary tuberculosis.

Haematogenous spread of tuberculosis to skin

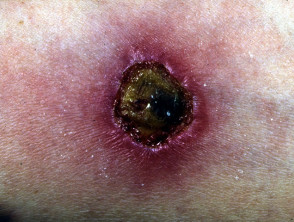

Metastatic tuberculous abscess (tuberculous gumma) is also due to haematogenous spread to the skin in children and immunocompromised adults, but presents as a subcutaneous nodule or cold abscess on an extremity. The overlying skin breaks down to form an ulcer with sinus tracts and fistulae.

Extension into the skin from an underlying infective focus

Scrofuloderma follows the direct invasion of the skin from tuberculosis in an underlying lymph node or bone, often in association with pulmonary TB. The most common sites involved are around the neck and under the jawline.

Scrofuloderma

| Types of cutaneous tuberculosis | Features |

|---|---|

| Tuberculosis verrucosa cutis |

|

| Lupus vulgaris |

|

| Scrofuloderma |

|

| Miliary tuberculosis |

|

| Orificial tuberculosis |

|

Dermoscopy of cutaneous tuberculosis

Lupus vulgaris: pink-red background, white structureless areas, yellow-white globules, white scale, short and long linear vessels, and branching telangiectases. Follicular keratotic plugs are not seen, helping to distinguish lupus vulgaris from lupus miliaris disseminatus faciei.

What are the complications of cutaneous tuberculosis?

Some forms of cutaneous tuberculosis are associated with low immunity to M. tuberculosis, and may indicate an immunocompromised state or severe underlying infection that may be fatal.

Rarely, primary cutaneous tuberculosis can disseminate or, following healing, lupus vulgaris or tuberculosis verrucosa cutis can appear at the same site.

Tuberculids are hypersensitivity reactions that typically develop in patients with moderate to high levels of immunity to the tubercle bacillus.

Lupus vulgaris and scrofuloderma can be destructive and heal with disfiguring scars. Lupus vulgaris can be complicated by the development of squamous cell carcinoma or other skin cancers in the scar 25–30 years later in up to 10% of patients.

Complications of cutaneous tuberculosis

How is cutaneous tuberculosis diagnosed?

The diagnosis of cutaneous tuberculosis is usually made or confirmed by characteristic histopathological features on skin biopsy. Typical tubercles are caseating epithelioid granulomas that contain acid-fast bacilli (AFB). However, in some forms of cutaneous tuberculosis these can be very difficult to locate due to very low numbers of bacilli in the skin.

Tubercle bacilli can be detected in the skin by special tissue stains such as Ziehl-Neelsen, polymerase chain reaction (PCR), and culture in the laboratory.

Other tests that may be necessary include:

- Tuberculin skin test (Mantoux or PPD test)

- Interferon-gamma release assay (IGRA) blood test such as QuantiFERON-TB gold

- Sputum culture (it may take a month or longer for results to be reported)

- Chest X-ray and other radiological tests for extrapulmonary infection.

Severe Mantoux test reactions (active TB)

What is the differential diagnosis of cutaneous tuberculosis?

- Tuberculous chancre: atypical mycobacterial infection, other opportunistic infections

- Lupus vulgaris: leprosy, sarcoidosis

- Tuberculosis verrucosa cutis: viral wart, keratoses

- Orificial tuberculosis: Crohn disease, syphilis

- Scrofuloderma: atypical mycobacterial infections, abscess.

What is the treatment of cutaneous tuberculosis?

Patients with pulmonary or extrapulmonary TB need an adequate course of appropriate multi-drug anti-tuberculous treatment. This usually involves a combination of isoniazid, rifampicin, pyrazinamide, and ethambutol given over a period of six months for a standard course. Multi-drug resistant tuberculosis has become a significant problem worldwide. New anti-tuberculous drugs are being developed, including bedaquiline which has FDA approval.

Patients with latent TB infection but no active disease may also be treated with anti-tuberculous drugs to prevent development of active disease. [See Tuberculosis screening].

Single drug therapy is discouraged.

Occasionally surgical excision of localised cutaneous TB such as lupus vulgaris or scrofuloderma is recommended. Plastic surgical reconstruction may be required by some patients disfigured by lupus vulgaris.

What is the outcome of cutaneous tuberculosis?

Spontaneous healing can occur for tuberculous chancre, scrofuloderma, and tuberculosis verrucosa cutis. Lupus vulgaris is usually progressive if untreated, as are most cases of tuberculosis verrucosa cutis, and scrofuloderma. Some presentations of cutaneous tuberculosis, such as miliary tuberculosis, indicate significant systemic disease which may be fatal.

Treatment is usually successful with an adequate course of appropriate multi-drug therapy, although some skin lesions are slow to heal.