What is malaria?

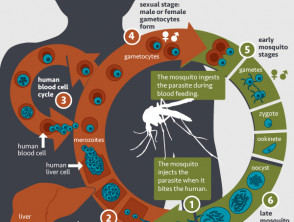

Malaria is a blood-borne tropical infection caused by parasitic protozoa of the genus Plasmodium transmitted between people via infected female Anopheles mosquitoes.

Who gets malaria?

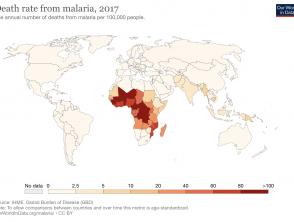

Malaria only occurs in the 91 tropical and subtropical countries where the Anopheles mosquitoes can survive, multiply, and complete their growth cycle. Disease incidence within these countries further depends on environmental factors including altitude, climate, and vegetation. In 2016, the World Health Organisation (WHO) estimated 90% of malaria cases in the world occurred in sub-Saharan Africa, but other regions at risk included South-East Asia, Central and South America, and parts of the Middle East. The WHO World Malaria Report for 2019 estimated 229 million cases and 409,000 deaths in that year.

Children under 5, pregnant women, and the immunosuppressed are at the highest risk of contracting malaria.

As malaria is a blood-borne disease, it is possible to contract it from blood transfusions and the sharing of needles, but this is rare.

What causes malaria?

Malaria is caused by just four of the many species of Plasmodium protozoa. These are:

- P. falciparum

- P. vivax

- P. malariae

- P. ovale.

The Plasmodium protozoa are spread by the female Anopheles mosquito which bites between dusk and dawn. The mosquito deposits the protozoa in the intervascular skin matrix, from where the microorganisms invade the bloodstream and rapidly establish infection in the liver. The parasites mature and multiply in the liver over several days before entering red blood cells for their final growth phase. The infected red cells burst open to release protozoa into the bloodstream where another mosquito can incidentally collect them during a blood-feed. This phase of parasitaemia, when many parasites are circulating in the blood, corresponds to an acute attack of symptoms.

What are the clinical features of malaria?

Symptoms of malaria usually develop 10–15 days after an infectious mosquito bite (range 7 days to 3 months). An acute attack of uncomplicated malaria lasts 6–10 hours and presents with fever, chills, headache, cough, myalgia, abdominal pain, vomiting, and diarrhoea. Progression to severe malaria involves organs including the brain, kidney, or lungs, or blood disturbances such as severe anaemia, metabolic acidosis, hypoglycaemia, or disseminated intravascular coagulation (DIC).

What are the cutaneous features of malaria?

Apart from the visible mosquito bites, cutaneous findings are rare and non-specific in malaria, but have been reported with P. falciparum and P. vivax malaria. Reported cutaneous findings include:

- Urticaria

- Angioedema

- Petechiae

- Purpura

- Reticulate erythema over the limbs sparing palms and soles.

Mucosal involvement has not been reported.

Skin signs may indicate complications such as jaundice, anaemia, and DIC.

Skin side effects of malaria treatment and chemoprophylaxis

Tetracyclines can cause photosensitivity including photo-onycholysis. Photosensitivity is an important adverse effect in tropical countries, and appropriate sun protection should be recommended when doxycycline is prescribed for chemoprophylaxis in travellers.

Hydroxychloroquine can cause morbilliform or psoriasiform rashes in up to 10% of people.

What are the complications of malaria?

Uncomplicated malaria can progress to severe disease, with organ involvement including:

- Pulmonary oedema and acute respiratory distress

- Acute renal failure

- Cerebral malaria, epilepsy, reversible post-malaria neurological syndrome, and permanent visual, motor, or language disorders

- Hyper-reactive malarial splenomegaly (very enlarged spleen) and splenic rupture.

P. falciparum malaria in pregnancy can cause severe disease in the mother resulting in premature delivery or low birth-weight baby. Congenital malaria is due to transplacental infection from the mother or during delivery and presents in the first 48 hours after birth. Neonatal malaria presents three weeks after birth following an infected mosquito bite. Both forms carry a high mortality rate.

Relapses can occur months or years after P. vivax or P. ovale infection following reactivation of dormant liver parasites.

How is malaria diagnosed?

Malaria should be considered in anyone with a febrile illness in an endemic area, or after visiting an endemic area in the previous 12 months.

Malaria is diagnosed on microscopic examination of a blood film. Thick blood film examination provides sensitivity. Thin blood film examination allows speciation and quantitation. If the initial film is negative, blood should be reassessed every 6–12 hours for 36–48 hours before malaria can be confidently excluded.

Antigen-based rapid diagnostic tests (RDT) detect specific antigens produced by the parasite. Some are species specific, while others can detect multiple species.

What is the differential diagnosis for malaria?

Malaria presents as a nonspecific acute febrile illness. The differential diagnosis therefore is long and includes many other tropical infectious febrile illnesses, including:

- Dengue fever

- Typhoid fever

- Brucellosis

- Leishmaniasis

- African/American trypanosomiasis

- Rickettsial diseases.

What is the treatment for malaria?

The best treatment option for malaria is prophylaxis including clothing, netting over beds, mosquito repellents, and chemoprophylaxis with medications such as doxycycline and hydroxychloroquine, depending on the geographic location. Work on vaccine development continues.

Vector control to prevent the spread of mosquitoes can include:

- The destruction of areas of stagnant water where mosquitoes breed

- Treatment of houses and netting with insecticide

- Release of sterile male mosquitoes

- Genetic modification of mosquitoes to reduce disease susceptibility.

General measures

Treatment may be required for:

- Secondary infection

- Electrolyte and fluid imbalance

- Anaemia

- Hypoglycaemia.

Antihistamines have been reported to ease the symptoms of cutaneous involvement.

Supportive measures for complications may also include ventilation and/or dialysis.

Specific measures

The medication used for prophylaxis and treatment will depend on drug resistance and severity of disease. Drugs used include:

- Doxycycline

- Clindamycin

- Hydroxychloroquine and chloroquine

- Artemisinin derivatives, such as artesunate and artemether.

What is the outcome for malaria?

Full recovery from malaria is expected with appropriate prompt treatment. However, treatment is not always curative due to drug resistance, high parasite density, treatment noncompliance, low host immunity, and poor drug bioavailability. Recurrent symptoms with detectable parasitaemia can occur 2–6 weeks after apparently successful treatment.

Urticaria is reported to subside 12–48 hours after starting antimalarial treatment. All skin symptoms resolve within days of treatment without recurrence.

Cerebral malaria and anaemia in children can result in persistent movement disorders, speech difficulties, deafness, blindness, behavioural issues, and epilepsy.

Severe malaria can deteriorate rapidly, with death within hours or days due to missed or delayed diagnosis, but also sometimes despite appropriate treatment and intensive care.

P. falciparum malaria can be rapidly fatal within 24–48 hours of presentation, especially in children.

In 2018, there were an estimated 228 million cases of malaria, and 405,000 deaths (mostly children) worldwide.