What is Mohs micrographic surgery?

Mohs micrographic surgery, or Mohs surgery, is a precise surgical technique in which the complete excision of skin cancer is checked by microscopic margin control. It offers the highest cure rates while maximizing preservation of healthy tissue. The principles behind it were developed by Dr Frederic Mohs in the 1930s.

Mohs surgery is recognised as the treatment of choice for high risk basal cell carcinoma and squamous cell carcinoma. The skin cancer is progressively removed in stages. After each stage, the excision margins are microscopically examined for remaining cancer cells and this process is repeated until all cancer has been removed.

Mohs is a form of complete circumferential peripheral and deep margin assessment (CCPDMA).

What is the difference between Mohs surgery and standard excision?

In standard excision, the tissue sample is sent off for histological processing while the wound is closed. The processing takes a number of days during which cross sections (or vertical sections) are created at various distances through the sample and are microscopically assessed by a pathologist. The pathologist looks for skin cancer at the margins of each section, but these are only a fraction of the actual excision margin.

In Mohs surgery, the histological processing takes place on the day of surgery and the wound is only closed after it has been confirmed that the entire cancer has been removed. The excision margin is examined by an embedding technique that allows horizontal sections to be cut involving all the deep and radial excision margins. If any tumour is visible in these sections, it means that the excision is incomplete and the patient requires a further Mohs stage.

A mapping process and colour coding system is used during Mohs surgery to precisely localise any remaining cancer, and tissue is only removed if it contains cancer. This process preserves healthy tissue.

Mohs surgery yields higher clearance rates than standard excision, and smaller wounds — therefore better cosmetic results.

The steps involved in Mohs surgery

Mohs surgery is usually undertaken as a single day procedure under local anaesthesia. It involves the following steps:

- The visible tumour plus a small margin is outlined using a skin marker, and a reference map or grid is drawn on the patient (often using temporary sutures).

- The area is excised at an angle of 30–45 degrees at the radial margins.

- Haemostasis is obtained and the wound is temporarily dressed.

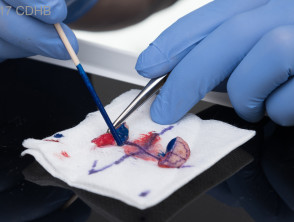

- The excised tissue sample is divided in two or more sections that are colour coded using special tissue dyes.

- A mapping process ensures that residual tumour seen under the microscope can later be matched to the exact location on the patient using a paper based map or digital photographs and image processing software (see example).

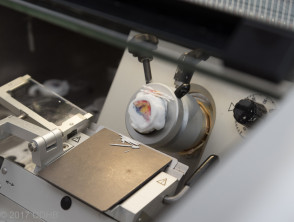

- A specialised histotechnician or biomedical scientist embeds and freezes the tissue in a cryostat to create horizontal sections of the entire excision margin.

- The Mohs surgeon examines the microscopic sections for remaining cancer.

- Any remaining cancer is precisely drawn on the map or digital image.

- This map or image is then used to identify the area on the patient from which more tissue needs to be removed.

- See step 2. The process is repeated until the patient is tumour free.

- The wound is closed, see wound closure topic for an overview of techniques.

See clinical images of Mohs surgery ...

What types of skin cancer are best treated by Mohs surgery?

Mohs surgery is widely accepted as treatment of first choice for high risk basal cell carcinoma and squamous cell carcinoma. Although different criteria are used across the globe, the main reason to perform Mohs is to minimise the risk of incomplete excision. This reduces burden to the patient and may avoid large and costly re-excisions later.

Mohs surgery has greatest benefit for a tumour at high risk of incomplete excision, such as a:

- Recurrent or incompletely excised tumour

- Tumour arising in skin previously exposed to radiotherapy

- Large tumour, especially in the head and neck area

- Tumour that has poorly defined clinical borders

- Basal cell carcinoma with an aggressive growth pattern on histology (infiltrative, micronodular or with perineural invasion)

- Squamous cell carcinoma at higher risk of metastasis (eg, located on ear, lip; with perineural invasion; or in a patient that is immune suppressed)

Mohs may also be appropriate when a large reconstruction is needed to close the defect or when the tumour is located in a cosmetically sensitive area.

In 2012, a joint effort by various medical organisations in the USA led to the development of appropriate use criteria for Mohs surgery. These criteria may be used as guidance when considering Mohs surgery although they may not apply in all jurisdictions [1].

Mohs for other types of skin cancer

There is plenty of evidence that Mohs is the best form of surgery for high risk basal cell carcinoma and squamous cell carcinoma. Large trials comparing Mohs to standard excision for other types of skin cancer are lacking.

In Mohs surgery, tumour cells must be accurately identified on microscopic examination of frozen sections. This can be challenging in some skin cancers, such as:

- Atypical fibroxanthoma

- Very poorly differentiated squamous cell carcinoma

- Dermatofibrosarcoma protuberans

- Microcystic adnexal carcinoma

- Lentigo maligna/melanoma in situ

- Extramammary Paget disease

For these tumours, variations of Mohs surgery may be applied that follow the basic principles of Mohs surgery (microscopic margin control, horizontal embedding, and mapping and colour coding of tissue) but use paraffin embedded sections instead of frozen sections. This allows the use of immunohistochemical markers to help identify tumour cells.

Such techniques are sometimes collectively referred to as slow Mohs. They include the 'Tuebingen Cake', and 'Muffin' techniques [2].

How effective and cost effective is Mohs surgery?

Mohs surgery leads to fewer tumour recurrences than standard excision of basal cell carcinoma and squamous cell carcinoma. Recurrence rates for Mohs are typically reported to be 1–5%, depending on type of tumour and length of follow-up.

In a randomised clinical trial with 10-year follow-up, recurrence rates were:

- 4.4% for Mohs surgery and 12.2% for standard excision for high risk primary basal cell carcinoma

- 3.9% for Mohs and 13.5% for standard excision for high risk recurrent basal cell carcinoma [3].

Several studies have also found that Mohs is more cost effective than standard excision. The main reason for this is that there are fewer costly operations for recurrent tumours compared to standard excision [4-5].