What are radiographic investigations?

Radiographic investigations produce images of tissues and bones under the skin. The term is often used to include a variety of imaging methods using X-rays, computed tomography (CT) scans, ultrasound scans, and magnetic resonance imaging (MRI).

Radiographic investigations in melanoma

Why are radiographic investigations in melanoma important?

There are benefits for melanoma patients from radiographic investigations, such as the early detection of metastases or for reassurance, but there are also risks, such as detection of unimportant lesions (false-positives) or missed metastases (false negatives). Follow-up should include evaluation of any symptoms and examination of the site of the original tumour and regional lymph nodes. Regular skin examinations are also important as radiographic investigations rarely detect new primary melanomas.

There are three key indications for radiographic investigations of patients with melanoma.

- Initial staging of a patient with melanoma to determine if high-risk cancer has spread to any internal body sites

- To evaluate the response to treatment (eg, targeted therapies and immunotherapies) [1–3]

- To monitor patients after melanoma resection for patients at high risk of recurrence or progression with the aim of detecting early recurrence [1].

Guidelines and standards indicate that investigations are not indicated for melanoma in situ (Stage 0) or thin invasive melanoma (Stage I or II) with no clinical symptoms or signs of metastasis. The appropriate patients for staging or surveillance are those at significant risk for distant metastases [4].

Although primary melanoma tumours and local metastases in the lymph nodes or in-transit can often be detected on clinical examination, clinical monitoring for deep lymph nodes and distant viscera is more difficult. Distant visceral metastatic disease is often asymptomatic until advanced, when it may be difficult to remove surgically [1].

What radiographic investigations are used in the staging and surveillance of malignant melanoma?

Basic radiological investigations such as chest x-ray (CXR) can detect occult metastatic melanoma, but their two-dimensional soft-tissue views are limited [5]. Thus many patients will be referred for CT, positron emission tomography-CT (PET-CT), ultrasound imaging, and MRI scans.

Computed tomography and positron emission tomography-CT

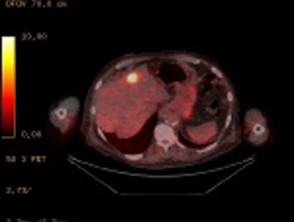

CT and PET-CT scans are commonly used in staging and surveillance of many solid malignancies.

- CT provides three-dimensional views of the body.

- PET-CT adds a fluorodeoxyglucose (FDG) tracer, which highlights areas of increased metabolically activity frequently seen with solid malignancies including melanoma.

- PET-CT provides incremental information to CT alone as it can detect metabolically active disease in tissues such as lymph nodes which may appear structurally normal on CT.

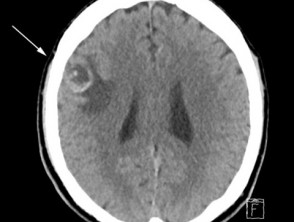

- PET-CT can accurately detect metastases in most body sites, except the brain where there is high background metabolic activity and diagnostic CT or MRI is superior [6].

Ultrasound imaging

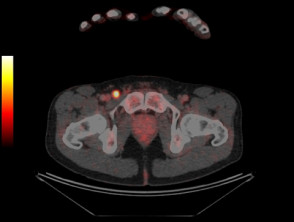

Ultrasound imaging is used to monitor regional lymph node basins for metastases. The accuracy of ultrasound is dependent upon the skill and experience of the sonographer [7,8].

Magnetic resonance imaging

MRI provides high-resolution imaging.

- It is used to look for metastatic disease in the brain.

- MRI may be also used to investigate suspicious areas seen on PET-CT prior to surgery or biopsy [9].

Which patients should undergo radiographic investigations for melanoma surveillance?

Radiographic investigations are appropriate for patients with stage III metastatic melanoma, where there has been histologically confirmed spread of melanoma to lymph nodes, in-transit metastases, or satellite metastases. These patients are at high risk of recurrence or progression to stage IV metastatic melanoma [10–12]. The relative poor mortality of stage IIC melanoma also merits consideration of surveillance [12].

- International guidelines for surveillance imaging in melanoma patients are inconsistent as they are based upon expert consensus rather than evidence.

- The results of published research studies are difficult to compare because they have enrolled patients with melanoma at differing stages.

- Until recently, there were no effective systemic treatment options, so there was little interest in evaluating radiographic investigations. This has changed with the development of targeted therapies and immunotherapies.

- The American National Comprehensive Cancer Network (NCCN) recommends CT or CT-PET scans 3–12 monthly for patients with asymptomatic stage IIB–IV melanoma [13].

- The European Society of Medical Oncology recommends only physical examination every three months [14].

Ultrasound surveillance of the regional nodal basin can be considered for:

- Surveillance for recurrence in patients who have a positive sentinel lymph node biopsy and who have not undergone complete lymph node dissection.

- Surveillance in those who have not had a sentinel lymph node biopsy but remain at high risk of progression to stage III disease due to unfavourable characteristics of the primary tumour.

- Initial staging of the lymph node basin; however, ultrasound is not as accurate as sentinel lymph node biopsy [15–17].

Ultrasound surveillance in stage I or II melanoma is superior to the clinical examination of the regional lymph node, but the long-term survival benefit of ultrasound surveillance is unknown [8]. Only a few patients benefit from earlier detection of lymph node metastasis or avoidance of unnecessary surgery, and some undergo unnecessary surgery for suspicious findings [8].

What are the benefits of radiographic investigations for melanoma surveillance?

Isolated metastases detected by surveillance or staging imaging can be potentially cured by surgical resection, radiotherapy, or systemic therapies [18–20], and patients have superior survival rates with modern therapies [21–23].

- In Australian data, PET detected metastases up to six months earlier than other imaging or physical examinations [24].

- Two studies showed a patient’s treatment changed in 19–35% of stage III melanoma patients following PET-CT scans [25–27]

- PET-CT and CT are also able to detect additional primary malignancies [28–29].

Other advantages of selected imaging modalities

- Ultrasound imaging is non-invasive and does not emit radiation.

- MRI does not emit radiation, unlike CT scans.

What are the controversies and disadvantages of radiographic surveillance of melanoma?

Without a randomised trial, it is difficult to prove that melanoma survival is superior in those who have undergone imaging.

Even after negative imaging, patients or their partners detect the majority of recurrences in melanoma as they are often visible or palpable within the skin or lymph nodes [30,31].

- The detection rates for imaging of asymptomatic distant metastases vary between 15 and 72% depending on staging [31–33].

- PET-CT rarely detects metastatic disease smaller than 5 mm [34–36].

- The benefit of PET-CT in detecting occult metastases in sentinel lymph node-positive patients ranged from 0.5 to 3.7% [37–40].

There is a risk that surveillance imaging may detect non-specific lesions or result in false-positive findings for metastasis [1,41].

- Additional invasive investigations may be undertaken when there are non-specific findings or false positives [41,42].

- PET surveillance in stage IIIA metastatic melanoma patients has been associated with a 7–14% false-positive rate [1,43,44].

- In one of these studies, 86% of these false-positive findings underwent biopsy [1].

Multiple studies have evaluated the overall accuracy of PET-CT staging and surveillance.

- Sensitivity and specificity of PET-CT was 65% and 99% for regional disease, 86% and 91% for distant metastasis, and 80% and 87% for staging respectively [45].

- Ultrasonography had the highest sensitivity (60%) and specificity (97%) for the staging of regional lymph nodes and 96% and 99% for targeted lymph node respectively [45].

- The reliability of PET and CT brain in detecting brain metastasis is poor [46,47]. In one study of almost 700 patients with cutaneous metastatic melanoma, 12% were found to have asymptomatic brain metastases on CT scan [48].

- MRI brain is superior for evaluation of intracranial metastatic disease but is contraindicated in patients with metal implants.

- A single PET-CT detected 24% of recurrences in asymptomatic melanoma in 110 asymptomatic patients with stage IIB to IIIB melanoma [44].

- In 170 patients undergoing PET-CT surveillance imaging, melanoma recurrence was identified in 38%, of which 69% were asymptomatic. A negative PET-CT at 18 months had negative predictive values 80–84% for true non-recurrence at any time in the 47-month (median) follow-up period [1]. Of the PET-CT detected recurrent patients, 33 (52%) underwent potentially curative resection, although only 16% remained disease-free after 24 months [1].

How often should surveillance scans be performed?

The optimum frequency for surveillance scans — and for how long — are unknown.

- Typically, PET scans are performed every 6 months for surveillance of high-risk patients [1,23].

- Most recurrences of melanoma occur within the first two to three years [1,11].