What are sunbeds?

Sunbeds are artificial tanning devices used to tan or darken skin. They may be in the form of a lie-down bed or an upright cubicle that the user stands in.

Sometimes the term 'solarium' may be used, but this is generally applied to a commercial establishment offering sessions on a sunbed.

How do artificial tanning devices work?

Some light tubes surround the user so that their body receives a relatively uniform exposure on all sides. Other tanning devices include portable sun lamps that are positioned in front of or angled over the skin. Like the sun, the light tubes in artificial tanning devices, such as sunbeds and sunlamps, emit ultraviolet (UV) radiation as well as some visible light.

The intensity of the UV radiation emitted by the lamps in a sunbed, and the relative proportions of ultraviolet A (UVA) and ultraviolet B (UVB), depends on how the bulbs are manufactured and may vary with the pressure of the gas in the light tube and differing inner coatings. UV radiation from a sunbed may vary quite markedly from UV radiation from the sun. It may, for example, have a much higher proportion of UVA than sunlight, and be far more intense, meaning that skin is damaged faster than after exposure to the sun.

Are sunbeds safe to use?

The International Agency for Research on Cancer (IARC) has classified natural UV radiation and UV-emitting tanning devices (sunbeds) as carcinogenic [1]. A systematic review published in 2012 [2] found that:

- People who have used a sunbed have a 20% greater risk of melanoma than those who have not

- Those who first used a sunbed before the age of 35 years have a 59% greater risk of developing melanoma

- The risk of melanoma was calculated to increase by 1.8% with each additional sunbed session per year

- 5.4% of melanoma cases in European countries could be attributed to sunbed use [2].

A more recent study of Norwegian women supports the findings of higher melanoma risks in sunbed users and in those who used sunbeds from an early age, and also found that women who first used sunbeds before the age of 30 years were diagnosed with melanoma at a younger age than women who had never used sunbeds [3].

The link between skin cancer and UV radiation exposure is quite simple — the greater the exposure to UV radiation, the greater the likelihood of developing skin cancer and the more quickly the skin will age. (For further information on the effects that UVA and UVB have on skin, see our page on sunburn.)

The only time an artificial tanning device should be used is in the medical procedure of phototherapy. This process of exposing the body to UV radiation is useful in the treatment of some skin conditions, including psoriasis and dermatitis. These treatments should be conducted under medical supervision.

Addiction to tanning

Some people determined to expose their skin to natural or indoor sources of UV radiation are considered to be addicted to the habit. A study published in 2017 reported that, when compared to non-users, tanning-dependent individuals were six times more likely to be dependent on alcohol, five times more likely to exhibit 'exercise addiction' and three times as likely to suffer from seasonal affective disorder [4].

What standard and guidelines cover sunbeds and their commercial use?

Australia/New Zealand Standard for commercial solaria

The Australian/New Zealand Standard: Solaria for cosmetic purposes (AS/NZS 2635:2008), is intended to “provide operators and users of artificial tanning equipment with procedures for reducing the risk associated with indoor tanning” [5]. It sets out a range of procedural and administrative measures on how commercial sunbeds should be operated, as well as the technical requirements and specifications for the sunbeds. The recommendations include [5]:

- The use of a client consent form that highlights the risks of exposure to UV radiation

- The requirement for a skin type assessment before accepting a client, and basing the tanning schedule on the client’s skin type

- The display of signs warning of the risks of UV exposure

- The use of goggles to protect eyes

- The disinfection of the sunbed between users

- Having trained staff on duty whenever the sunbed is being used

- Controlling the length of a sunbed session with a timer that can only be set by the operator

- Limiting the total UV output and the UVB component of the sunbed.

The New Zealand Ministry of Health published draft Guidelines to help operators comply with the Standard [6]. Since 2012, the Ministry of Health has asked public health staff to visit sunbed operators to try to improve their compliance. (The findings from these visits are available for download from the Ministry of Health's website [7]).

Compliance with the Standard is voluntary in most parts of New Zealand, but in Auckland, many of the requirements have been mandated in the Auckland 2014 Health and Hygiene Bylaw [8].

The International Standard for sunbed manufacture

The most widely recognised International Standard applying to sunbeds is International Electrochemical Commission's Household and similar electrical appliances — Safety — Part 2–27: Particular requirements for appliances for skin exposure to ultraviolet and infrared radiation. (IEC 60335-2-27) [9]. (Some countries have adopted this under their national Standards framework, with small variations to suit local conditions.) The Standard is part of a series covering electrical safety of appliances and covers tanning beds intended for both commercial and home use.

The features of the IEC 60335-2-27 Standard include the following [9]:

- It distinguishes between sunbeds intended for commercial and domestic use; the maximum allowed UV output (irradiance) for domestic sunbeds is lower than for commercial models, and in a domestic sunbed both the UVA and UVB components must be below set limits

- It specifies how the UV exposure is measured

- It specifies a comprehensive set of instructions and warnings that must be provided in the user manual

- It requires that sunbeds be marked to show the UV lamp equivalency code range for replacement lamps (more details on this follow in the next section).

The International Standard for sunbed lamps

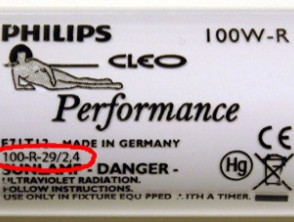

The International Electrotechnical Commission's Fluorescent ultraviolet lamps used for tanning — Measurement and specification method (IEC 61228) [10] specifies how the UV output of sunbed lamps should be measured, taking into account the relative effectiveness of UV radiation at causing skin cancer as a function of wavelength (the action spectrum). It also defines a marking scheme for the lamps as a means to ensure that when bulbs in a sunbed are replaced, the new bulbs have similar characteristics. The equivalency code specified in the Standard has the format: wattage/reflector type/UV code.

- The "wattage" is the nominal lamp wattage.

- The four "reflector types" are O (non-reflector), B (broad-reflector angle), N (narrow-reflector angle) and R (a rectangular reflector).

- The UV code is marked "X/Y". "X" means the erythemally effective UV irradiance wavelength is in the range 250–400 nm in mW/m2. "Y" means the Non-Melanoma Skin Cancer (NMSC) effective irradiance is at wavelengths ≤ 320 nm)/(NMSC effective irradiance at wavelengths > 320 nm). This is effectively the UVB:UVA ratio.

For example, in the figure below, the lamp has the equivalency code of 100-R-29/2.4.

Example of an equivalency code marked on a sunbed lamp

The code means that:

- The nominal wattage is 100 W

- It has a rectangular reflector

- The erythemally effective UV at wavelengths from 250–400 is 29 mW/m2

- The ratio of NMSC effective UVB: NMSC effective UVA is 2.4.

Sunbeds that satisfy the IEC 60335-2-27 Standard must be marked to show the equivalency codes of the lamps to which can be used in them. For example, if the sunbed were manufactured and tested with the tubes shown above, the fluorescent UV lamp equivalency code range marked on the sunbed would be equivalence code interval '100-R-(22–29)/(2.0–2.8). This means that any 100 W reflector tubes with erythema weighted irradiance between 22 and 29 and a UVB/UVA ratio between 2.0 and 2.8 could be used in the sunbed.

In general, if the equivalency code of the tubes in the sunbed when it was tested was '100-R-X/Y', the allowable range of X in replacement tubes is 0.75 X–X, and the allowable range of Y in replacement tubes is 0.85 Y–1.15 Y.

What regulations govern the use of sunbeds?

A variety of approaches has been used around the world to try and manage the risks from sunbed use, including:

- A complete ban on commercial sunbed operations

- Restrictions on use (based on age, skin type, or supervision requirements)

- Licensing operators

- Limiting the UV intensity and exposure times

- Taxing sunbed sessions

- Providing information about the risks (eg, requiring warning signs and a consent form, and restricting or banning promotion).

The World Health Organization has information on its Global Health Observatory website about sunbed legislation in different countries [11]. The WHO has also published a booklet on public health interventions to manage sunbeds, which provides examples of the approaches taken in different countries [12].

In Australia, commercial sunbeds have been banned since 2016. In New Zealand, use of sunbeds and solaria by people under 18 years of age has been prohibited since January 2017. Compliance with the New Zealand Standard for sunbed and solaria operating procedures is otherwise voluntary.

What are the myths surrounding the use of sunbeds?

Many myths are surround the use of tanning devices, some of which are dispelled below.

Sunbathing or using a sunbed will help to build up vitamin D

Most people get sufficient vitamin D from their diet and incidental exposure to sunlight during their day-to-day routine. Seek medical advice if you have concerns about not getting enough. A consensus statement published by the New Zealand Ministry of Health and the Cancer Society of New Zealand recommends against the use of sunbeds to boost vitamin D because of the increased risk of melanoma.

Getting a tan from a sunbed will provide good skin protection against sunburn

A tan from a sunbed only provides minimal protection against the effects of sun exposure. It has been estimated that a tan only offers the same protective effect as using a sun protection factor 2 sunscreen.

I cannot get skin cancer and premature ageing of the skin if I get a tan but don't burn

UVA, unlike UVB, does not cause the early signs of sunburn but it does penetrate the lower layers of the skin and induce premature ageing, which can manifest as roughening, blotchiness, and wrinkling. UVA also suppresses the skin's immune system, which may play a role in the development of skin cancers. Thus, you can still develop skin cancers years after exposure to a sunbed, even if you don't get visible sunburn.

Sunbed use prevents the onset or retards the growth of cancers

Sunbed use is believed by some people to help prevent cancers such as breast cancer, prostate cancer, colon cancer, osteoporosis, and other diseases. There is no scientific evidence to indicate that sunbed usage lowers the chance of developing tumours or other diseases in humans.