What is Lynch syndrome?

Lynch syndrome (OMIM 120435) is the most common inherited syndrome that predisposes to cancer. It is also known as hereditary non-polyposis colorectal cancer (HNPCC), of which Muir-Torre syndrome (OMIM 15832) is a rare specific variant.

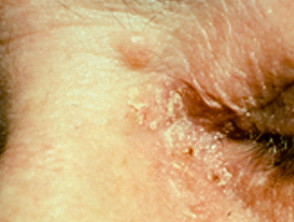

Sebaceous carcinoma in Muir-Torre syndrome

Figure 1 Reproduced from: Kim JE, Kim JH, Chung KY, Yoon JS, Roh MR. Clinical features and association with visceral malignancy in 80 patients with sebaceous neoplasms. Ann Dermatol. 2019;31(1):14–21.

Figure 2 Reproduced from: Lynch MC, Anderson BE. Ileocecal adenocarcinoma and ureteral transitional cell carcinoma with multiple sebaceous tumors and keratoacanthomas in a case of Muir-Torre syndrome. Dermatol Res Pract. 2010;2010:173160.

Who gets Lynch syndrome?

Lynch syndrome affects one in 350 individuals, including white, Asian, and African populations.

Muir-Torre syndrome (MTS) is more commonly reported in males (3:2) with an average age of onset of skin manifestations being 53 years (range 21–88 years).

Ultraviolet radiation, radiotherapy, and drug-induced immunosuppression (particularly tacrolimus and ciclosporin), such as in transplant recipients, may unmask latent Muir-Torre syndrome.

What causes Lynch syndrome?

Lynch syndrome is caused by impaired DNA mismatch repair (MMR), leading to DNA microsatellite instability (MSI) and the accumulation of DNA mutations in oncogenes and tumour suppressor genes, ultimately leading to cancer. The genes involved in human mismatch repair are MLH1, MLH3, MSH2, MSH3, MSH6, PMS1, and PMS2.

Germline mutations in any one of these genes may result in Lynch syndrome, although the spectrum of malignancies may be different for each gene.

Muir-Torre syndrome is currently described as a phenotypic variant of Lynch syndrome, representing 1–2% of cases. It is usually due to mutations in the MSH2 gene (90%). MLH1 and MSH6 gene mutations have been reported but are rare in MTS. An autosomal recessive variant with microsatellite stability has been identified.

Turcot syndrome is another variant of Lynch syndrome, presenting as colonic adenomas and tumours of the central nervous system, with mutations mainly found in MLH1 and PMS2 genes.

What are the clinical features of Lynch syndrome?

Lynch syndrome is associated with a spectrum of malignancies including colorectal, stomach, pancreas, endometrium, ovary, urological (renal pelvis, ureter, prostate), and brain. Numerous skin tumours are described in Lynch syndrome, particularly in the Muir-Torre variant. Skin lesions may be one of the first signs of Lynch syndrome and represent 3–5% of the extracolonic cancers.

Cutaneous manifestations of Lynch syndrome

- Sebaceous gland tumours are the characteristic skin sign of Muir-Torre syndrome and, although typically located on the periocular area, in MTS they may occur on any skin site.

- Sebaceous adenoma – benign skin tumour; present as slow-growing yellow papules and nodules; often central umbilication with ulceration; most specific and commonest skin marker of Muir-Torre syndrome affecting 2/3

- Sebaceoma (sebaceous epithelioma) – similar clinical presentation to sebaceous adenoma but distinguished on histology; affects 1/4

- Sebaceous carcinoma — develops in 1/3; extraocular location is usual in Muir-Torre syndrome

- Basal cell carcinoma with sebaceous differentiation

- Sebaceous hyperplasia and sebaceous naevus are not related to MTS

Sebaceous adenoma in Muir-Torre syndrome

Figure 4 Reproduced from: Wargo JJ, Plaza JA, Carr D. Sebaceous neoplasia leading to the diagnosis of Muir-Torre syndrome in an African American man. JAAD Case Rep. 2021;11:72-3.

Figure 5 Reproduced from: Kim JE, Kim JH, Chung KY, Yoon JS, Roh MR. Clinical features and association with visceral malignancy in 80 patients with sebaceous neoplasms. Ann Dermatol. 2019;31(1):14–21.

- Other skin lesions

- Multiple keratoacanthomas — is considered part of the Lynch/Muir-Torre syndrome spectrum; histology often shows sebaceous differentiation in MTS

- Cutaneous squamous cell carcinoma (cSCC) — is not defined in the syndrome spectrum but large case studies have identified an increased risk of cSCC in patients with Lynch syndrome

- Multiple follicular or epidermoid cysts

- Fordyce spots

Dermoscopy of sebaceous adenoma and sebaceoma

- Arborising vessels or radial telangiectases

- White-yellow background

- Structureless ovoid white-yellow centre or loosely arranged yellow comedo-like globules

What are the complications of Lynch syndrome?

Lynch syndrome is characterised by the development of multiple malignancies, often at a young age, which can metastasise and may be fatal. Sebaceous carcinomas can be locally invasive and metastasise.

How is Lynch syndrome diagnosed?

Clinical diagnosis of Lynch syndrome is based on Amsterdam II or Revised Bethesda Guidelines and confirmed on genetic testing.

Amsterdam II Criteria:

- Three or more relatives with histologically verified Lynch-associated cancers, excluding familial adenomatous polyposis

- Cancer involving at least two generations

- One or more cancer cases diagnosed before the age of 50 years.

Muir-Torre syndrome is defined by the constellation of sebaceous tumours, multiple keratoacanthomas, and other Lynch-associated malignancies. A detailed family history including first and second-degree relatives should be taken. Sebaceous tumours are diagnosed on skin biopsy [see Sebaceoma pathology, Sebaceous carcinoma pathology]. MTS should be considered in anyone under 50 years of age with a solitary sebaceous adenoma, multiple sebaceous tumours, or a sebaceous tumour not on the head and neck, and investigated initially by tissue immunohistochemistry.

Investigations may include:

- Immunohistochemistry on tumour tissue for MMR deficiency and MSI

- DNA sequencing of excised tumour tissue

- Genetic testing of peripheral blood.

Genetic testing of family members may identify individuals at risk of Lynch syndrome and therefore requiring appropriate surveillance.

What is the differential diagnosis for Lynch syndrome?

- Basal cell naevus syndrome (Gorlin syndrome)

- Birt–Hogg–Dubé syndrome

- Cowden disease

- Tuberous sclerosis

What is the treatment for Lynch syndrome?

Patients with Lynch syndrome require regular surveillance for Lynch-associated malignancies such as GIT endoscopy, urine cytology, imaging, and others. The age at which specific screening begins is guided by family history. It is recommended colonoscopy be performed every 1–2 years starting at age 20–25 years or 2–5 years before the earliest colorectal cancer in the family. Any cancers found should be treated appropriately eg, surgery, radiotherapy, chemotherapy, and/or immunotherapy.

Aspirin 600mg/d has been reported to decrease the risk of colorectal cancer in Lynch syndrome. Sirolimus has been recommended for patients with MTS requiring immunosuppression after a transplant.

Annual skin examination should be performed with excisional biopsy of suspicious lesions. Keratoacanthoma-like lesions should be fully excised and not watched in the expectation of spontaneous resolution. Sebaceous carcinoma requires Mohs micrographic surgery or wide local excision, with careful evaluation and follow-up of lymph nodes.

Patients with Lynch syndrome should be educated regarding symptoms and signs that may indicate malignancy such as for ovarian or endometrial cancer.

What is the outcome for Lynch syndrome?

Early detection and treatment of cancers in patients with Lynch syndrome improves survival. The internal malignancies may behave in a less aggressive manner than would be predicted based on their histology. Sebaceous carcinoma has a local or metastatic recurrence rate of up to 25%.