What is a skin biopsy?

A skin biopsy is the removal of a sample of skin. It is usually undertaken using a local anaesthetic injection into the skin to numb the area. The injection stings transiently. After the procedure, a suture or dressing may be applied to the site of the biopsy.

Why have a skin biopsy?

A skin biopsy may be deemed necessary as part of the diagnostic process. The additional information obtained from the biopsy can help identify diagnostic clues that are invisible to the naked eye.

Types of skin biopsy

Punch biopsy

Punch biopsy

The punch biopsy is generally the most useful type of biopsy. It is quick to perform, convenient, and only produces a small wound. It creates a full thickness sample of skin that allows the pathologist to get a good overview of the epidermis, dermis, and most of the time, the subcutis also.

A disposable skin biopsy punch is used, which has a round stainless steel blade ranging from 2–6 mm in diameter. The 3 and 4 mm punches are the most common sizes used. The clinician holds the instrument perpendicular to the anaesthetized skin and rotates it to pierce the skin. Using a forceps and scissors the skin sample is subsequently removed.

A suture may be used to close a punch biopsy wound or help control bleeding. If the wound is small, it may heal adequately without it.

Shave biopsy

A shave biopsy may be used if the skin lesion is superficial, for example to confirm a suspected diagnosis of intraepidermal carcinoma or basal cell carcinoma.

A tangential shave of skin is taken using a scalpel, special shave-biopsy instrument or razor blade. No stitches are required. The wound forms a scab that should heal in 1–3 weeks.

As a shave biopsy does not include the full thickness of the skin, the drawback of such a biopsy is that it may be difficult for a pathologist to rule out or identify invasive disease.

A scoop biopsy is a deep form of shave biopsy, used to remove a skin lesion such as a benign mole by "scooping" it out. It is also called “saucerisation” or “tangential excision”. Because of the increased depth, this type of shave biopsy may lead to more extensive scarring if left to heal by secondary intention. In some cases, it may require stitches afterwards.

Curettage

A skin curette may be used to scrape off a superficial skin lesion, such as a seborrhoeic keratosis. Some of the curettings are sent for histopathology. These samples are not suitable for determining if a lesion has been completely removed.

Incisional biopsy

Incisional biopsies refer to removal of a larger and generally deeper ellipse of skin, using a scalpel blade. Stitches are usually required after an incisional biopsy. This type of biopsy may be useful to provide a better overview for the pathologist, which can improve diagnostic accuracy. It can also be useful when deeper layers or tissue are believed to be involved in the disease process (eg, subcutaneous fat or medium-sized blood vessels).

Excision biopsy

Excision biopsy refers to complete removal of a skin lesion, such as a skin cancer in which a margin of surrounding skin is taken to improve chances of complete removal. Smaller lesions are most often removed using a scalpel blade as an ellipse, with primary closure using sutures. Larger excisions may be repaired using a skin flap (moving adjacent skin to cover the wound) or graft (skin taken from another site to patch the wound).

Choosing the type of and site for a biopsy

It is crucial that the site of a biopsy is chosen carefully, or the pathological diagnosis could be incorrect or misleading. Here are a few guidelines to help find the best site, some general advice and pitfalls to avoid, depending on the type of skin lesion.

For suspected skin cancer:

- A punch biopsy will generally give the pathologist the best sample of skin to determine the growth pattern and depth of invasion. A 3 mm punch will suffice in most cases.

- Avoid taking a biopsy from the centre of the lesion if it is ulcerated. It will be more difficult to suture the wound if it bleeds plus the tissue may be largely necrotic which makes it harder to obtain a proper tissue sample.

- If there is a lot of scale present, gently remove this first and take the biopsy from immediate underlying skin.

- It is generally not recommended to try and remove a skin cancer completely using a punch biopsy.

For most inflammatory skin diseases:

- A punch biopsy generally provides a good overview of the entire skin for the pathologist and usually a 4 mm punch is sufficient.

- As lesions evolve over time they will exhibit more (or less) useful features upon histological examination so when choosing a biopsy site the age of a lesion is an important aspect to consider.

- When vasculitis is suspected the best lesion to biopsy is a fresh one (between 24 and 48 hours of age).

- In general, it is best to take a biopsy from the centre of a larger, well-developed site. It should be taken from the elevated edge of an annular plaque.

- Avoid areas that are scratched/excoriated as these will show nonspecific changes.

- Avoid areas that have been treated with topical steroids or other anti-inflammatory agents when possible.

For ulcers, erosions and blisters:

- Skin adjacent to erosions and ulcers usually provides the most useful diagnostic information.

- When blisters are present, a biopsy is best taken from the edge of a blister, while including two-thirds of normal adjacent skin.

- A small intact blister may show more useful information than the corner of a large one

- A punch biopsy taken for immunofluorescence purposes is best taken from perilesional skin.

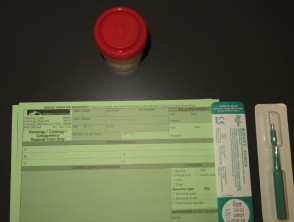

Completing the request form

The clinician should ensure the pathology request form includes basic patient information (including age and identification details), the site and type of biopsy, and time and date. Left and right are best written out in full to avoid mistakes

In addition to this, it is crucial for the pathologist to be provided with clinical information and a range of possible diagnoses. For best clinicopathological correlation clinical information should include a description of the duration, symptoms and a dermatologic description.

The sample pot should be labelled with patient identification details, the body site of the biopsy, time and date, and checked against the request form for consistency. When multiple biopsies are taken roman numbers are best used to match the request forms with their corresponding sample pots.

Request form

What happens to the biopsy sample?

Most skin biopsies are placed in formalin in a small pot and are sent to the lab for paraffin fixation, processing and histopathological examination.

- If considering deep fungal infection or mycobacteria, the sample may be divided so that one part of the sample is sent in formalin for histopathology and the other is placed on a saline-soaked gauze swab for microbiology.

- Samples for direct immune fluorescence are placed in transport media, snap frozen in liquid nitrogen, or sent “fresh” (eg placed on a moistened gauze swab in a sterile empty pot).

Complications of skin biopsy

Skin biopsy is usually straightforward and complications are uncommon. As a general rule, the larger the skin sample removed, the higher the chance of complications. The following complications might occur.

Bleeding

Intraoperative or postoperative bleeding can occur in anyone, but can be particularly troublesome in those with a bleeding tendency, or taking blood-thinning medications such as warfarin or aspirin.

Infection

Bacterial wound infection affects about 1–5% of excisional biopsies. It is however extremely uncommon in small punch, shave or incisional biopsies. Ulcerated or crusted skin lesions, site of biopsy, patient characteristics such as diabetes, older age, or use of immunosuppressive medicines may contribute to increased risk of infection.

Nerve injury

The blade may cut a superficial sensory nerve causing pain or numbness. This is most likely to occur where the skin is thin, for example on the face or back of hand. Risk of motor nerve impairment is extremely rare, but can occur during skin cancer surgery in facial danger zones. These include the temporal, marginal mandibular, zygomatic branches of the facial nerve and the spinal accessory nerve (at Erb's point).

Scarring

It is usual for a biopsy site to form a significant permanent scar. Some body sites such as the centre of the chest are prone to develop excessive or hypertrophic scars. This is also more common in Afro-Caribbean skin types.

Persistence or recurrence of the skin lesion

Many biopsies are deliberately partial and only intended for diagnostic purposes. In excisional biopsies there is a risk of not removing the full lesion, which may recur later.

Anaesthetic problems

Allergies to local anaesthetics are a possibility but are also extremely rare. A vasovagal reaction is more common, which may cause the patient to faint and potentially hurt him or herself. Palpitations are another side effect which are related to the adrenalin commonly present in the local anaesthetic.

Wound breakdown

This is an uncommon complication of sutured wounds. It is more likely to occur in body sites where there is a lot of tension of the scar (eg, chest, back), immediately after suture removal, or as a result of infection. Avoidance of exercise, use of strappings and dissolvable sutures may help prevent this.

Obtaining the results of the biopsy

It usually takes about one or two weeks to obtain the result from the pathology laboratory, but can sometimes take longer if special stains or second opinions are required. The pathologist describes what is observed under light microscopy in several sections of the biopsy sample, and either makes a diagnosis or assists in differentiating between the suggested range of clinical diagnoses.

Clinicopathological correlation

Skin diseases and conditions can at times be very difficult to diagnose accurately. In those cases the clinical and histopathological findings combined form a more complete picture to make a correct diagnosis. This is called the clinicopathological correlation. Many organisations hold regular multidisciplinary meetings (MDMs) at which clinical information, clinical photographs, and pathology slides are reviewed by a team of experts to determine the best diagnosis and treatment for the patient.