What is direct immunofluorescence?

Direct immunofluorescence (DIF) is a technique used in the laboratory to diagnose diseases of the skin, kidney, and other organ systems. It is also called the direct immune fluorescent test or primary immunofluorescence.

DIF involves the application of antibody–fluorophore conjugate molecules to samples of patient tissue obtained from biopsies. These antibody–fluorophore conjugates target abnormal depositions of proteins in the patient’s tissue. When exposed to light, the fluorophore emits its own frequency of light, seen with a microscope. The particular staining pattern and type of abnormal protein deposition seen in the tissue sample help diagnose the disease.

Direct immunofluorescence for the diagnosis of skin diseases

DIF is useful in the diagnosis of suspected autoimmune disease, connective tissue diseases and vasculitis. The staining patterns seen in tissue samples may be specific to a disease entity or they may need to be interpreted with the clinical and histological findings.

Autoimmune bullous diseases

DIF is useful in diagnosing the following autoimmune bullous diseases:

- Pemphigus vulgaris

- Pemphigus foliaceus

- Paraneoplastic pemphigus

- Immunoglobulin (Ig) A pemphigus

- Bullous pemphigoid

- Pemphigoid gestationis

- Mucous membrane pemphigoid (cicatricial pemphigoid)

- Epidermolysis bullosa acquisita

- Bullous systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE)

- Linear IgA bullous disease

- Dermatitis herpetiformis.

Connective tissue diseases

DIF is useful in diagnosing the following connective tissue diseases:

- Lupus erythematosus (systemic, discoid, and subacute cutaneous forms)

- Neonatal lupus erythematosus

- Systemic sclerosis

- Mixed connective tissue disease

- Dermatomyositis.

Vasculitis and other conditions

DIF is useful in diagnosing cutaneous vasculitis and some other types of inflammatory skin disease:

- Small vessel (hypersensitivity) vasculitis

- Henoch–Schönlein purpura

- Lichen planus

- Porphyria cutanea tarda

- Some adverse cutaneous reactions to drugs

- Photosensitivity rashes

Site of biopsy

The optimal site for taking a biopsy of the skin depends on the suspected disease.

- Autoimmune bullous diseases: take normal-appearing perilesional skin less than 1 cm from a bulla. As false-negative results may arise from samples from the lower extremities, avoid these sites if possible.

- Connective tissue diseases: the biopsy should be taken from an established lesion (often in sun-exposed areas), ideally that is more than 6 months old but still active. An additional specimen is often taken in a sun-protected site.

- Vasculitis: for best results, take a punch biopsy or a deep-shave biopsy of a lesion that is less than 24 hours old.

Another biopsy is usually taken for routine haematoxylin–eosin (H&E) histology. Note that the optimal biopsy site and timeframe required differs for these examples.

- Autoimmune bullous diseases: remove an entire vesicle or biopsy the edge of a bulla.

- Vasculitis: select a purpuric lesion of fewer than 72 hours duration.

Transport and storage of the biopsy sample

Specimens for DIF should not be placed in formalin, as this alters proteins and significantly diminishes the accuracy of results. Transport the specimen to the laboratory as soon as possible. Options for transporting the sample include:

- Placed on a saline-soaked gauze

- In saline solution

- In special media (eg, Michel or Zeus media)

- Frozen in liquid nitrogen (the specimen should not be allowed to thaw).

Each laboratory has its own protocols. Specimens in saline may yield superior sensitivity over other media if processed within 24–48 hours.

What happens to the specimen in the laboratory?

DIF may be carried out in an automated machine or manually. The process involves first making frozen sections then carrying out immunofluorescence.

Preparing frozen sections

- A punch biopsy is transported to the lab on saline-soaked gauze.

- The specimen is placed in a gel.

- Liquid nitrogen is used to freeze the specimen and gel.

- The frozen specimen is contained within the frozen gel.

- The specimen can be stored in liquid nitrogen for about one week.

- 4–6 micron thick slices are cut.

Preparing frozen sections

Carrying out direct immunofluorescence

- Five or six slides are made; each for a different reagent. One slide will be used for a normal H&E stain.

- A special pen is used to draw a perimeter to keep reagents within the slides.

- The slides are washed.

- The reagents are made up.

- The reagents (antibody–fluorophore conjugates to IgG, IgM, IgA, complement protein C3, and when required fibrinogen) are dropped onto the slides and the slides are left for some time in the dark.

- The slides are washed again in solution.

- Glass covers are placed over the slides.

Carrying out direct immunofluorescence

Interpretation of direct immunofluorescence

The prepared immunofluorescence slides are examined by a pathologist to determine the primary sites of immune deposition (if any), the classes of immunoglobulin or other immune deposits, and the patterns of deposition. Staining patterns can be classed into five groups:

- Intercellular surface staining (ICS) pattern

- Linear basement membrane zone (BMZ) pattern

- Granular BMZ pattern

- Shaggy BMZ pattern

- Vascular and other patterns.

Immunofluorescence patterns in skin diseases

Examples of staining patterns

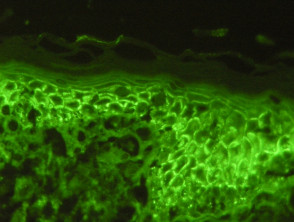

- Intercellular space staining pattern (chicken-wire), pemphigus vulgaris.

- Intercellular space staining pattern (chicken-wire), pemphigus foliaceus.

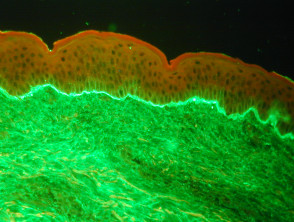

- Linear IgG deposition on basement membrane zone, bullous pemphigoid.

- Linear IgA deposition on basement membrane zone, linear IgA bullous dermatosis.

- Vascular staining pattern in dermal vessels for IgM.

- Granular C3 deposition on basement membrane zone

Staining patterns of specific skin diseases

Pemphigus vulgaris

- ICS pattern IgG (90–100%) or C3

Pemphigus foliaceus

- ICS pattern IgG or C3

Paraneoplastic pemphigus

- Weak ICS pattern

- Linear or granular BMZ IgG or C3

- Sometimes, lichenoid change

IgA pemphigus

- ICS with IgA

Bullous pemphigoid

- Linear BMZ with IgG and linear BMZ with C3

Mucous membrane pemphigoid (cicatricial pemphigoid)

- Linear BMZ with IgG, C3, and IgA

Epidermolysis bullosa acquisita

- Linear BMZ IgG and C3

- Sometimes, linear BMZ IgA or IgM

Dermatitis herpetiformis

- Granular BMZ with IgA

- Sometimes, granular BMZ C3

- Rarely, granular BMZ IgG and M3

Lupus erythematosus

- Systemic lupus erythematosus

- Granular BMZ IgG, IgM, IgA, C3

- Speckled epidermal nuclei pattern IgG (10–15%)

- Discoid lupus erythematosus

- Granular BMZ IgG, IgM

- Cytoid bodies IgM and IgA

- Subacute cutaneous lupus erythematosus

- Granular BMZ IgG, IgM, C3

- Epidermal intracytoplasmic particulate deposition IgG

- Cytoid bodies IgM, IgA

Systemic sclerosis

- Granular BMZ IgM

- Speckled epidermal nuclei deposition (20%)

Mixed connective tissue disease

- Granular BMZ (15%)

- Speckled epidermal nuclei pattern IgG (46–100%)

Dermatomyositis

- Granular IgM, IgG, C3

- Cytoid bodies IgM, IgA

Lichenoid reactions (lichen planus, drug reactions and photodermatoses)

- Shaggy BMZ pattern for fibrinogen

- Cytoid bodies IgM, IgA

Porphyria cutanea tarda

- Dermal vessels: continuous thick staining IgG, IgA, C3

- Granular BMZ C3, IgM

- Linear BMZ IgG, IgA

Vasculitis

- Strong dermal vessels IgM, IgG, C3, fibrinogen

Henoch–Schönlein purpura

- Strong dermal vessels IgA

How reliable are direct immunofluorescence results?

DIF testing is moderately sensitive in detecting a range of diseases. The sensitivity for DIF approaches 100% for the pemphigus group of diseases, and sensitivity has been reported to be 55–96% for bullous pemphigoid. A study of ten patients with Henoch–Schönlein purpura and nine with lupus erythematosus demonstrated positive DIF testing in all of the patients.

The number of false-negative results with DIF depends on the quality of the sample, laboratory processing, and whether or not the patient has been on treatment. Reasons for false-negative results include:

- An incorrect site of biopsy

- Lack of epidermis in biopsy and other technical errors

- Prolonged storage of specimen before transport to the laboratory

- Photobleaching and other laboratory errors

- The patient is on active immune-modulating treatment.