Acknowledgement

This document incorporates and summarises information from a number of publications, including guidelines published by the National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE) [1,4], UpToDate [2,7,10,16,17,23,26] and the NZ Formulary [20,22]. It is relevant to the treatment of psoriasis in New Zealand.

In this guideline, psoriasis refers to chronic plaque psoriasis, unless otherwise specified.

What is psoriasis?

Psoriasis is a chronic inflammatory skin disorder that is characterised by disfiguring, scaling and erythematous plaques that may be itchy or painful. Although once thought of as a benign dermatological condition with few serious complications, psoriasis is now considered a multisystem inflammatory disease that is associated with, or increases, the risk of other comorbidities. Psoriasis can be both emotionally and physically debilitating and significantly impact the quality of life [1,2]. [see Psychological effects of psoriasis]

Who gets psoriasis?

The prevalence of psoriasis worldwide is 0.5% to 11.4% in adults, and 0% to 1.4% in children [3].

- Psoriasis is at a higher prevalence with increasing distance from the equator [2].

- The prevalence of psoriasis in New Zealand has not yet been established. Studies have shown the prevalence of psoriasis in adults to be 2.3% to 6.6% in Australia, and 1.3% to 2.2% in the United Kingdom [3,4].

- Rates of psoriasis vary between ethnic groups. A small study suggests that Maori and Pacific Islander peoples may be overrepresented in New Zealand compared to New Zealand Europeans [5].

- While most cases of psoriasis present before age 35, psoriasis can develop at any age [4].

- Males and females are equally affected by psoriasis [2].

What causes psoriasis?

Psoriasis is a complex immune-mediated disease. T lymphocytes, dendritic cells, cytokines and tumour necrosis factor are key in the pathogenesis [2].

- A genetic predisposition contributes to the development of psoriasis. Approximately 40% of people with psoriasis or psoriatic arthritis have an affected family member [2].

- Generalised pustular psoriasis has been associated with changes in the genes IL36RN, CARD14 and AP1S3 [6].

- Other risk factors for psoriasis include smoking, obesity and alcohol consumption [2].

- Medications can exacerbate psoriasis or cause a psoriasis-like rash. Examples include beta-blockers, lithium and antimalarial drugs. [see Drug-induced psoriasis] Certain bacterial and viral infections have also been linked to psoriasis [2].

What are the clinical features of chronic plaque psoriasis?

Chronic plaque psoriasis is the most common type of psoriasis in children and adults, accounting for 55–90% of cases [2,4]. The scalp, extensor elbows, knees and gluteal cleft are the most frequently involved sites. Plaques are erythematous with defined margins and often have a silvery scale. Scale is less evident after bathing or after the application of a moisturiser. The plaques are frequently pruritic. In people with darker skin, hyperpigmentation may be present [2].

What are the complications of chronic plaque psoriasis?

Approximately 7–42% of people with psoriasis develop psoriatic arthritis [10].

Comorbidities associated with psoriasis include obesity, metabolic syndrome, cardiovascular disease, malignancy, autoimmune disease (eg, inflammatory bowel disease, coeliac disease and diabetes), chronic kidney disease, non-alcoholic fatty liver disease (NAFLD) [see Liver problems and psoriasis], depression, and alcohol abuse [8,10].

Severe psoriasis can cause death, particularly extensive erythrodermic and pustular psoriasis [2].

How is psoriasis diagnosed?

Psoriasis is a clinical diagnosis. A skin biopsy can be considered when there is diagnostic uncertainty [2].

How is psoriasis assessed?

Psoriasis is assessed by evaluating:

- Its severity, using both objective and subjective measures

- The presence of psoriatic arthritis

- Associated features and comorbidities.

Psoriasis severity

An objective assessment of psoriasis severity can be made using the static Physician’s Global Assessment (see below) or the Psoriasis Area and Severity Index (PASI). The PASI is generally used in specialist settings [1].

| Induration |

0 - no plaque elevation above the normal skin |

| Erythema |

0 - no evidence of erythema, hyperpigmentation may be present |

| Scaling |

0 - no evidence of scale |

| Average score | 0 = clear, 1 = nearly clear, 2 = mild, 3 = moderate, 4 = severe and 5 = very severe |

The patient's assessment of the severity of their psoriasis can be assessed using the static Patient's Global Assessment (graded as clear, nearly clear, mild, moderate, severe or very severe) [1] or a validated self-assessed or patient-oriented PASI score.

Body surface area (BSA) affected can be classified as:

- Mild psoriasis: < 5% of BSA

- Moderate psoriasis: 5%-10% of BSA

- Severe psoriasis: > 10% of BSA.

(Note: 0.5% of BSA in adults is approximately equal to the palm of the patient’s hand, excluding fingers [11])

The following features may indicate severe psoriasis due to the impact on the quality of life:

- Involvement of visible areas, major parts of the scalp, genitals, palms or soles [see Scalp psoriasis, Genital psoriasis, Palmoplantar psoriasis]

- Onycholysis or onychodystrophy of at least two fingernails

- Pruritus leading to excoriation [12].

When assessing the impact of psoriasis on physical, psychological and social wellbeing, questions to consider include:

- How does having psoriasis affect the patient’s daily life at home, work or at school?

- How is the patient coping with psoriasis and are they using any treatments?

- How does the patient feel — depressed, anxious, worthless, lonely?

- How is psoriasis affecting the patient’s relationship with their partner, family, friends, and carers?

- Does the patient need further advice or support? [1]

Quality of life measurement is important to properly assess the full effect of an illness such as psoriasis on patients. Two dermatology specific tools to assess the impact on the quality of life are:

- Dermatology Life Quality Index (DLQI): a self-reported questionnaire that consists of 10 items. The final score ranges from 0 to 30. DLQI ≤ 10 indicates mild to moderate disease, and DLQI > 10 indicates severe disease [12].

- Children’s Dermatology Life Quality Index (CDLQI): adapted for children age 4 to 16, and identical in structure to the DLQI. The child can complete it independently or with help from their caregiver [1].

Presence of psoriatic arthritis

People with psoriasis should be screened for psoriatic arthritis annually. This is best achieved in primary care and specialist settings through the use of a validated tool, such as the Psoriasis Epidemiology Screening Tool (PEST) [1]. Consider a non-urgent rheumatology referral or seeking rheumatology advice if the score is > 2 [1,8].

| Question | Yes | No |

| Have you ever had a swollen joint (or joints)? | 1 | 0 |

| Has a doctor ever told you that you have arthritis? | 1 | 0 |

| Do your fingernails or toenails have holes or pits? | 1 | 0 |

| Have you had pain in your heel? | 1 | 0 |

| Have you had a finger or toe that was completely swollen and painful for no apparent reason? | 1 | 0 |

| Consider referral to rheumatology with a score > 2 | ||

Associated features and comorbidities

Adults

Assess risk factors and comorbid disease of psoriasis at presentation and as indicated thereafter.

- Cardiovascular risk factors, and management of these (eg, smoking cessation)

- Measure blood pressure, lipid studies and fasting glucose at least annually.

- Risk of venous thromboembolism and its management [1].

- Depression and its management

- Alcohol consumption

- Signs of lymphoma, skin cancer, and solid tumours, according to guidelines for age, immune suppression, and phototherapy [10]

Children

Children with psoriasis [see Paediatric psoriasis] may have higher rates of associated comorbid disease. Recommended screening for risk factors and comorbid disease depend on the child’s age [15].

- All ages — psoriatic arthritis, lipids, annually for depression and anxiety

- From age 2 — annually for elevated body mass index (BMI)

- From age 3 — annually for hypertension

- From age 10 — 3 yearly for diabetes in patients who are obese or overweight and have 2 or more risk factors for diabetes; screen for NAFLD in those who are obese or overweight with additional risk factors for NAFLD.

- From age 11 — annual substance abuse screening [15]

Eye conditions may occur more commonly in people with psoriasis (blepharitis, conjunctivitis, xerosis, corneal lesions and uveitis). Consider asking patients about ocular symptoms at each follow-up appointment [2].

What is the differential diagnosis for chronic plaque psoriasis?

- Seborrhoeic dermatitis

- Atopic dermatitis

- Superficial fungal infections eg, tinea corporis

- Cutaneous T-cell lymphoma

What is the treatment for psoriasis?

While psoriasis is treatable, there is no cure [8]. Successful management is dependent on the patient understanding the chronic nature of psoriasis and the therapeutic options that are available to them. Points to consider include:

- Reassuring the patient and the patient’s family that psoriasis is not contagious.

- Determining how the patient perceives their disability and their preference and commitment to therapy.

- Discussing the risks and benefits of treatment options.

- Providing general advice regarding the benefits of not smoking, avoiding excessive alcohol intake, and maintaining a healthy weight and blood pressure [1,17].

- Advice to avoid direct pressure on areas of psoriasis where possible.

- The benefits and risks of sun exposure [8].

Treatment targets for plaque psoriasis

An acceptable treatment response is either BSA ≤ 3% or an improvement in BSA ≥ 75% from baseline, 3 months after treatment initiation [18].

The ideal target for treatment response is BSA ≤ 1% 3 months after treatment initiation maintained at every 6-month assessment interval during maintenance therapy.

Referral to specialist

Referral to a dermatologist for advice or face-to-face assessment is recommended in the following circumstances:

- Diagnostic uncertainty [1]

- Children with psoriasis at the time of diagnosis [1]

- Erythrodermic or generalised pustular psoriasis (emergency referral) or unstable psoriasis (urgent referral). Systemic symptoms (fever and malaise) may indicate unstable forms of psoriasis.

- Difficult to treat sites (face, genitalia, palms and soles) with inadequate response to initial treatment [1,8]

- Moderate to severe psoriasis likely to require phototherapy or systemic treatment

- Inadequate control using topical therapies alone

- Acute guttate psoriasis, for consideration of phototherapy

- Nail psoriasis with a significant functional or cosmetic impact [1]

- Significant impact on the quality of life, including a DLQI score > 9 [1,8]

- Any person who has psoriasis challenging to manage in the general practice (GP) setting [1,8].

Note: Public hospital dermatology services in NZ may have more stringent referral criteria due to a dermatology workforce shortage.

- Patients with ocular symptoms that may indicate an eye condition associated with psoriasis should be referred to an ophthalmologist [2,8].

- Patients with arthritis and PEST score ≥ 3 should be referred to a rheumatologist.

- Patients may also require assessment by a gastroenterologist if they have NAFLD or abnormal liver function tests on systemic medications for psoriasis.

Topical therapy

Consider patient preferences, cosmetic and practical aspects of treatment, and the body surface area affected [1].

- Discuss the different formulations available.

- An ointment is preferred for scaly plaques [1].

- Discuss referral for phototherapy or systemic therapy if patients are unlikely to respond adequately to topical therapy alone, including those with:

- Extensive psoriasis (> 10% BSA)

- A score of ‘moderate' or greater on the sPGA

- Nail psoriasis [1].

- Ensure the patient understands:

- Most people relapse without treatment [1,19]

- Once a satisfactory outcome has been achieved, treatments can be reduced to the amount needed to maintain psoriasis control [1]

- They should seek medical advice if the therapy is not tolerated, as the dose should be reduced or the therapy changed to an alternative [20].

- After a new topical therapy is started, arrange to review adults in 4 weeks and children in 2 weeks to:

- Assess the response to treatment, and how it has been tolerated

- Review adherence

- Highlight the importance of a break between courses of potent and very potent corticosteroids

- Identify the need for daily use of topical corticosteroids, which indicates that systemic therapy should be considered

- Discuss treatment alternatives if the response has been unsatisfactory [1].

- If the response has been unsatisfactory, consider the following:

- Difficulties with current therapy, such as tolerance, practical aspects of the application and cosmetic acceptability

- Other reasons for nonadherence

- Prescribing a different formulation [1].

- Review psoriasis patients at least annually to assess for adverse effects of steroid therapy, if:

- An adult is using potent or very potent corticosteroids

- A child using any form of corticosteroids [1].

Moisturiser

- Recommend emollients to all patients with psoriasis [19]. They improve dryness, scaling, and cracking and may have their own antiproliferative properties. They can be used with other treatments [20].

- Emollients may be all that is required to treat mild psoriasis.

- Emollients are especially beneficial for psoriasis of the palms and soles [20].

- Ointments and thick creams are most effective, particularly when applied straight after a shower or bath [17].

Soap substitute

- A soap substitute such as aqueous cream can help improve symptoms. The formulation of aqueous cream funded in NZ can also be prescribed as an emollient as it is sodium lauryl sulphate-free [8].

Coal tar

- Coal tar has anti-inflammatory and anti-scaling properties [20].

- Its use may be limited because it stains skin and clothes, is messy to apply, and has a strong smell [17].

- Coal tar sometimes causes irritation, contact allergy, and sterile folliculitis [20].

- Highlight the importance of shampoo formulations reaching the scalp [17].

Dithranol

- Dithranol is difficult to source in New Zealand.

- It is useful for the treatment of chronic plaque psoriasis in adults.

- Contraindications include acute psoriasis, pustular psoriasis, erythrodermic psoriasis and skin inflammation.

- It can cause localised irritation and staining of skin, nails and clothing.

- It is effective on large, thick plaques as ‘short-contact therapy’, where it is applied daily, initially with a contact time of 10 minutes which is steadily increased to 30 minutes over 7 days.

- It can also be used for scalp psoriasis [20].

Salicylic acid

- Salicylic acid is a keratolytic agent that reduces scaling and increases penetration of other topical treatments.

- It can be prescribed in combination with a topical corticosteroid or emollient. It is often already present in coal tar formulations.

- The recommended concentration is 2–5%.

- Salicylic acid is contraindicated in women who are pregnant. Use with caution in children under 5 years of age (a concentration < 0.5% can be used on limited areas), patients with widespread psoriasis, and patients with hepatic or renal impairment [21].

Calcipotriol

- Calcipotriol is a vitamin-D derivative.

- Calcipotriol is often used as first-line therapy for plaque psoriasis. It is also available in combination with topical betamethasone dipropionate and is available as gel, ointment and foam formulations.

- Contraindications to calcipotriol include calcium metabolism disorders and hypercalcaemia. Use with caution in generalised pustular, guttate and erythrodermic psoriasis where there is an increased risk of hypercalcaemia [20].

- Calcipotriol may cause irritation when applied to sensitive sites (eg, the groin).

- To avoid inactivation of calcipotriol:

- Apply calcipotriol and salicylic acid at different times, for example, one in the morning and the other in the evening

- Apply calcipotriol after phototherapy

- Avoid excessive sunlight [20].

- Maximum dose of calcipotriol in adults is 100 g/week, in children 12–18 years is 75 g/week, and in children 6–12 years is 50 g/week [20,22].

- Monitor serum calcium and renal function before commencing calcipotriol and 3-monthly following this if maximum doses may be exceeded [20,22].

Corticosteroid

- Topical corticosteroids have anti-inflammatory, antiproliferative and immunosuppressive properties through their effect on gene transcription [17].

- Match the strength and formulation to the patient’s preference and need [1].

- Improvement generally occurs with topical corticosteroids but the response is usually incomplete and the length of remission remains difficult to predict [17].

- Prolonged potent or very potent corticosteroid use may result in:

- Permanent striae and/or skin atrophy

- Unstable psoriasis [1]

- Adrenal suppression

- Paradoxical worsening of psoriasis [21].

- Potent corticosteroids should not be used continuously at any site for more than 4 weeks without a break. They can be used long term intermittently.

- Very potent corticosteroids should not be used for more than 4 weeks continuously. The advice of a dermatologist should be sought for ongoing use.

- A 4-week break is recommended between courses of potent or very potent corticosteroids (including when combined with calcipotriol). Offer an alternative topical treatment option during this time to maintain control of psoriasis if required (eg, calcipotriol or coal tar).

- Do not apply topical corticosteroids to more than 10% of BSA.

- Very potent corticosteroids are not suitable for children [1].

Tacrolimus and pimecrolimus

- Tacrolimus and pimecrolimus are calcineurin inhibitors.

- They will normally be initiated by a dermatologist or doctor with expertise in treating psoriasis.

- The most common side effects of tacrolimus and pimecrolimus are burning and itching that generally reduces with ongoing usage. Adverse effects also include erythema and skin infections. [20].

Tazarotene

- Tazarotene is a topical retinoid.

- It is best used in combination with topical corticosteroids.

- The most common side effect is skin irritation [17].

- Tazarotene is not available in New Zealand [20].

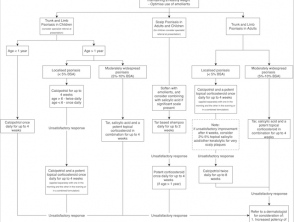

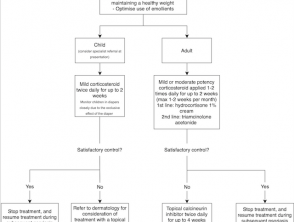

Flow charts for topical therapy

Download flow charts as PDF files:

- Topical treatment options for mild to moderate chronic plaque psoriasis of the trunk, limbs or scalp [1,8,17,19,21,22]

- Topical treatment options for mild to moderate chronic plaque psoriasis of the face or intertriginous areas [1,8,17,19,21–23].

Phototherapy

Phototherapy appears to slow keratinisation and reduce the activity of T cells implicated in the formation of psoriatic plaques [17].

- It is suitable for most people with an inadequate response to topical therapy [24].

- It can be given as monotherapy or in combination with topical or systemic agents [20].

- The types of phototherapy are narrowband ultraviolet B (UVB), broadband UVB, and psoralen plus ultraviolet A (PUVA) [1,17].

- Potential short-term side effects of phototherapy include:

- ‘Sunburn’ causing redness and irritation

- Dry, pruritic skin

- Folliculitis, usually mild

- Polymorphic light eruption

- Herpes simplex

- Blistering of psoriasis plaques

- Exacerbation of psoriasis

- Nausea with psoralen tablets (used in systemic PUVA) [25].

- Potential long-term side effects of phototherapy include:

- Premature ageing of skin [25]

- Skin cancer. Cancer risk has not been reported with narrowband UVB, however, it is possible that risk will be identified with longer follow-up [25,26].

- Phototherapy may not be an option for young children (< 5 years) or people with psychological or physical difficulties that preclude standing in the treatment booth.

- Narrowband UVB phototherapy is the most commonly used form of phototherapy [24]. UVB phototherapy is given 2 to 3 times a week for 6–12 weeks. Exposures are initially under a minute and are increased over time [1,24].

- The absolute contraindications to UVB phototherapy are lupus erythematosus and xeroderma pigmentosum [26].

- PUVA may be suitable for selected patients, such as those with localised palmoplantar pustulosis [1,20,24]. Psoralen amplifies the effect of UVA therapy and can be given orally or topically [20].

- The following should be discussed before commencing PUVA for psoriasis:

- Treatment alternatives

- The risk of skin cancer, which increases with the number of exposures [1]

- The total dose of phototherapy can be reduced by combining phototherapy with topical or systemic treatments (eg, coal tar, calcipotriol or oral acitretin) [1].

The following are indications for systemic treatment:

- Inadequate response to phototherapy

- Poor tolerance of phototherapy

- Rapid relapse after completion of phototherapy (> 50% of the baseline severity of psoriasis within three months)

- The patient is at high risk of skin cancer

- The patient has difficulty attending for phototherapy [1].

Traditional (non-biologic) systemic therapy

Systemic therapy should be initiated in a specialist setting. Monitoring and supervision can occur in non-specialist settings when these arrangements have been formalised and agreed upon [1].

The NICE guidelines suggest systemic non-biologic therapy should be offered to people with chronic plaque psoriasis if [1]:

- Psoriasis cannot be controlled with topical therapy; and;

- It has a significant impact on physical, psychological or social wellbeing; and;

- One or more of the following apply:

- The psoriasis is extensive (eg, >10% BSA is affected or a PASI score > 10)

- The psoriasis is localised and associated with significant functional impairment or high levels of distress (eg, severe nail psoriasis or involvement of high-impact sites)

- Phototherapy has been ineffective, cannot be used, or has resulted in rapid relapse.

Non-biologic systemic therapy outcomes can be optimised with the use of adjunctive topical therapy [1].

All patients using non-biologic systemic therapy need close monitoring for adverse effects, as per local protocols [20,22,24].

Non-biologic systemic agents include methotrexate, ciclosporin, acitretin, and apremilast.

Methotrexate

- Methotrexate is the first-line treatment for chronic plaque psoriasis [24].

- It is given as a once-weekly oral dose in adults and children.

- Contraindications include pregnancy, lactation, severe hepatic impairment, severe renal impairment and bone marrow depression [20].

- Patients require ongoing monitoring for haematological toxicity, hepatotoxicity and infection [20,24].

Ciclosporin

- Ciclosporin can be used in adults and children [20,22].

- It is used as a second-line treatment for chronic plaque psoriasis following methotrexate [24].

- It is also used for rapid control of psoriasis, palmoplantar pustulosis and those contemplating conception (males and females) who cannot avoid systemic treatment [1].

- Monitoring for nephrotoxicity and hypertension is essential [20,22,24].

Acitretin

- Acitretin is an oral retinoid agent, particularly useful for pustular psoriasis and as a third-line treatment after methotrexate and ciclosporin [1].

- It can be used in adults and children and is considered the treatment of choice in HIV-positive patients with psoriasis [17,20,22].

- Due to its high teratogenicity, it is contraindicated in pregnancy and has very limited use in women of childbearing age (strict contraception during treatment and for 3 years after stopping treatment).

- Acitretin has a number of adverse effects, including dryness of mucous membranes [24].

Apremilast

- Apremilast is a phosphodiesterase 4 inhibitor.

- It is a treatment option for moderate to severe chronic plaque psoriasis in adults [20].

- Evidence suggests apremilast is less effective than biologic agents [17].

- Apremilast is not subsidised in NZ [20].

Biologic systemic therapy

Biologic agents are effective in treating moderate to severe chronic plaque psoriasis. Studies show excellent short and long term results, and treatment is generally well tolerated [17]. While they are often more efficacious than non-biologic systemic therapies, the long term risks are still largely unknown. In addition, biologic systemic therapy is expensive, hence their use in clinical practice remains limited.

- Etanercept, adalimumab and infliximab inhibit the activity of tumour necrosis factor (TNF).

- Etanercept and adalimumab can be used in NZ for severe chronic plaque psoriasis refractory to standard treatments in both children and adults.

- Infliximab, secukinumab (an interleukin-17A inhibitor) and ustekinumab (an inhibitor of interleukins 12 and 23) are approved for severe plaque psoriasis refractory to standard treatments in adults only. Ustekinumab is not subsidised in NZ [20,22].

In New Zealand, a special authority application is required for a subsidy of biologic treatments [20,22].

- A dermatologist is required to apply on behalf of the patient.

- The eligibility criteria include having 'whole body' severe chronic plaque psoriasis with a PASI score of > 10 (> 15 for infliximab) or severe chronic plaque psoriasis of the face, palm or sole.

- The patient must also have had psoriasis for greater than 6 months and have trialled (or have contraindications to) at least three of the following treatments: phototherapy, methotrexate, ciclosporin and acitretin [27–30].

- General practitioners can renew applications if ongoing treatment is recommended by a dermatologist [24].

What is the outcome for psoriasis?

Psoriasis often has an unpredictable clinical course. Plaque psoriasis is generally a chronic disease, with fluctuating severity over time. Guttate psoriasis may resolve, relapse, or develop into chronic plaque psoriasis. Generalised pustular psoriasis frequently has a variable and protracted course without intervention [2].

Psoriasis is a multisystem inflammatory disease resulting in an increased risk of mortality compared to those unaffected by psoriasis [2,31]. Specifically, studies suggest an increased liver, kidney, infectious disease and chronic lower respiratory disease mortality risk. Patients with severe psoriasis also appear to have higher cardiovascular disease and neoplasm mortality risk [31]. The cause of the increased mortality risk is unknown. Postulated contributing factors include systemic inflammation, adverse effects of systemic treatments, comorbid conditions and behavioural risk factors [2,31]. Screening and holistic care may help minimise these risks.

We suggest you refer to your national drug approval agency such as the Australian Therapeutic Goods Administration (TGA), US Food and Drug Administration (FDA), UK Medicines and Healthcare products regulatory agency (MHRA) / emc, and NZ Medsafe, or a national or state-approved formulary eg, the New Zealand Formulary (NZF) and New Zealand Formulary for Children (NZFC) and the British National Formulary (BNF) and British National Formulary for Children (BNFC).